Introduction

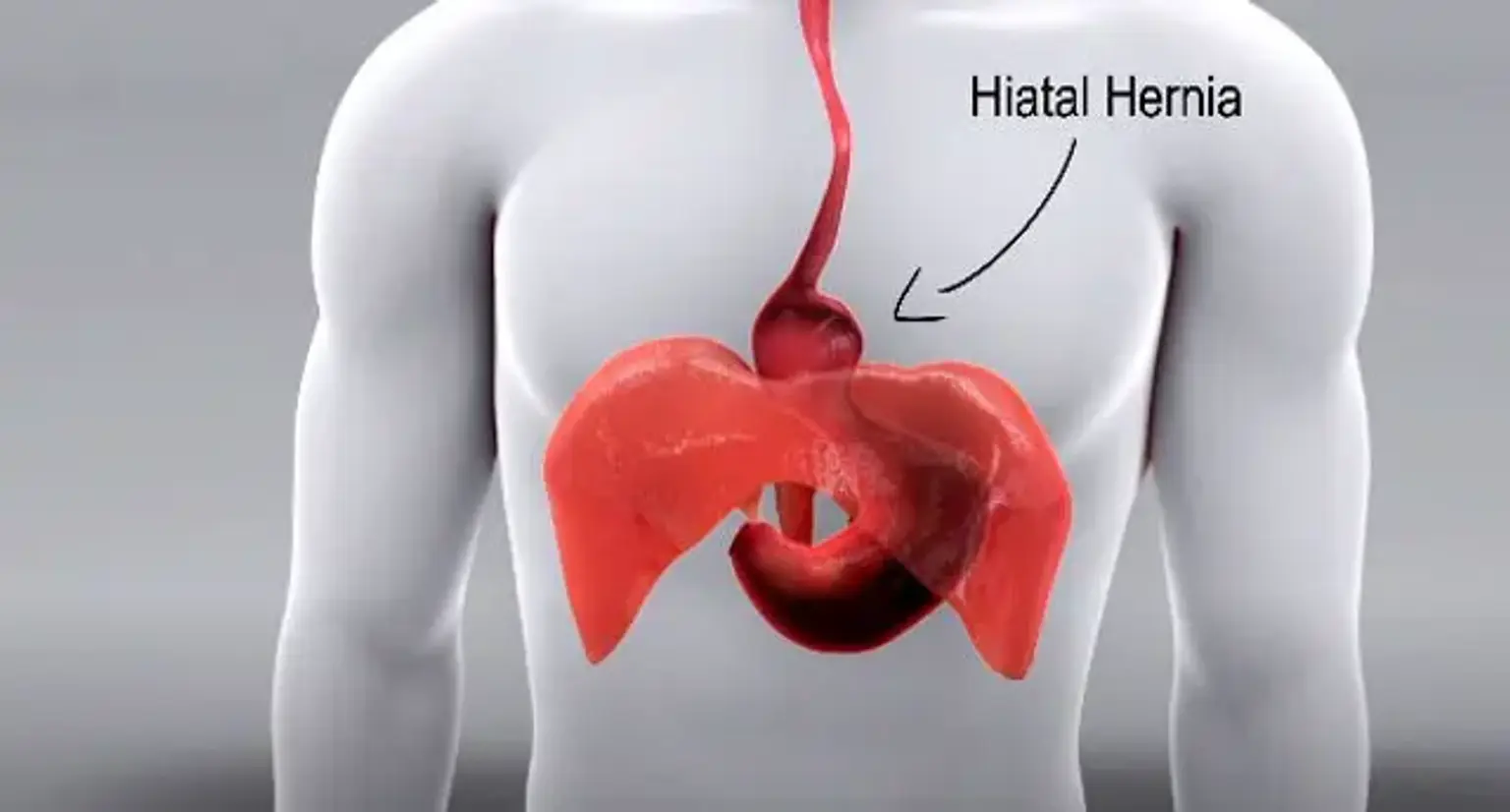

A hiatal hernia occurs when part of the stomach pushes through the diaphragm into the chest. Normally, the diaphragm helps keep the stomach in place, but when the opening in the diaphragm (esophageal hiatus) becomes enlarged, the stomach can move upward. This condition is more common in people over 50 and can cause symptoms like heartburn, chest pain, and regurgitation. In some cases, it can lead to serious complications like difficulty swallowing or esophageal damage.

This article will cover the causes, symptoms, diagnosis, treatment, and surgical options for hiatal hernias, focusing on advanced treatments like laparoscopic surgery available in Korea.

What is a Hiatal Hernia?

A hiatal hernia occurs when part of the stomach pushes up through the diaphragm. There are two main types:

Sliding Hiatal Hernia: The most common type, where the stomach and part of the esophagus move upward. This typically causes symptoms of acid reflux, such as heartburn.

Paraesophageal Hiatal Hernia: A more serious type where the stomach moves up beside the esophagus, which can lead to complications like strangulation and often requires surgery.

Both types can cause similar symptoms but vary in severity.