Overview of CPR

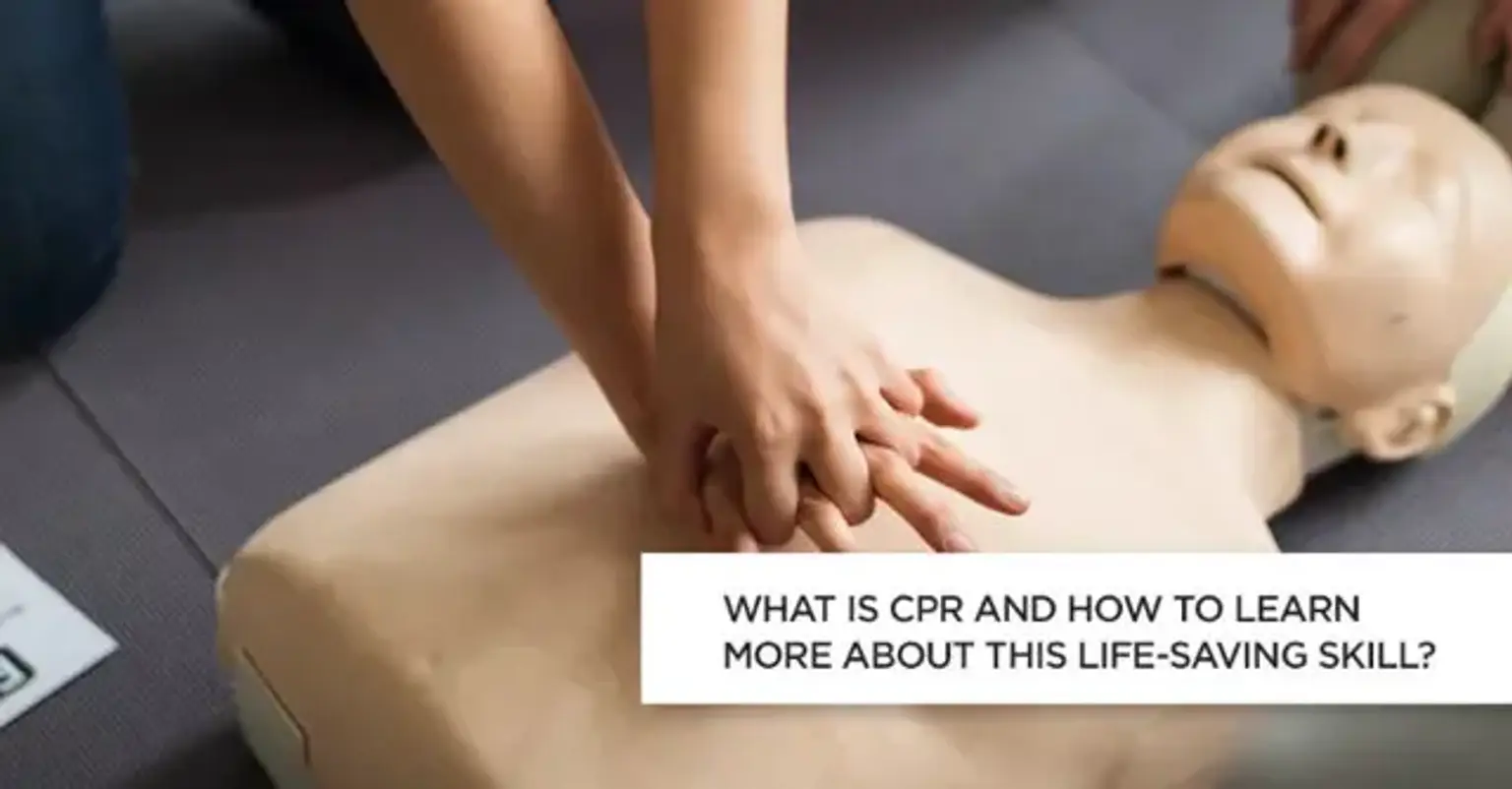

Cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) is a critical life-saving technique used in emergencies when someone's breathing or heartbeat has stopped, such as during cardiac arrest, drowning, or choking. CPR involves a combination of chest compressions and rescue breaths, which help maintain blood flow and oxygen delivery to vital organs until professional medical help arrives.

This technique is widely recognized as one of the most effective ways to increase the chances of survival in cardiac emergencies. From hospitals to homes and workplaces, the knowledge of CPR has saved countless lives, highlighting its importance as a fundamental skill for everyone.

Why CPR is a Vital Skill

Statistics show that immediate CPR can double or even triple the chances of survival for someone experiencing cardiac arrest. According to the American Heart Association (AHA), over 350,000 out-of-hospital cardiac arrests occur annually in the United States alone, with bystander intervention being a key factor in survival rates.

CPR is not just for healthcare professionals; anyone, regardless of age or profession, can learn it. This accessibility makes it one of the most empowering skills an individual can acquire. Learning CPR ensures that you are equipped to make a life-saving difference in a critical situation, whether for a stranger, friend, or family member.

What Happens During Cardiac Arrest?

Cardiac arrest occurs when the heart suddenly stops pumping blood due to an electrical malfunction. Unlike a heart attack, which is caused by a blockage in the blood vessels, cardiac arrest is a more immediate and life-threatening event. When the heart stops, oxygen-rich blood is no longer delivered to the brain and other organs, leading to rapid organ failure and death if left untreated.