Acute Otitis Media (AOM)

An infection of the middle ear canal is known as acute otitis media. Acute otitis media, chronic suppurative otitis media, and otitis media with effusion are all types of otitis media. After upper respiratory infections, acute otitis media is the second most common pediatric condition in the emergency room. Otitis media can affect anyone at any age; however, it is most frequent in children aged 6 to 24 months.

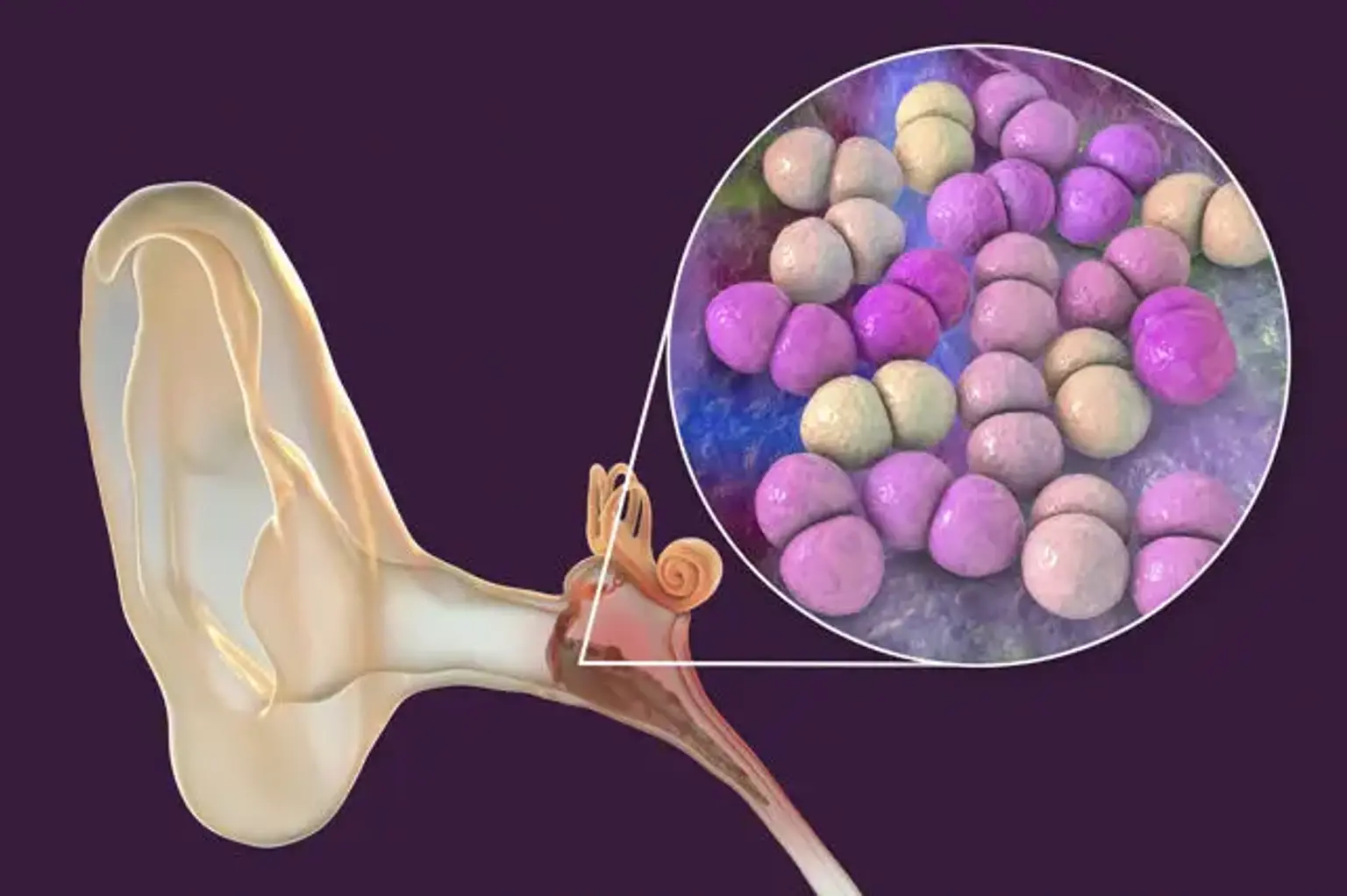

A viral, bacterial, or coinfection disease of the middle ear is possible. Streptococcus pneumonia is the most prevalent bacterial species that cause otitis media, followed by non-typeable Hemophilus influenzae and Moraxella catarrhalis. Pneumococcal organisms have evolved into non-vaccine serogroups after the advent of conjugate pneumococcal vaccinations. The respiratory syncytial virus, coronaviruses, influenza viruses, adenoviruses, human metapneumovirus, and picornaviruses are the most prevalent viral culprits causing otitis media.

Practically, otitis media is identified by combining objective findings on a medical examination (with otoscopy) with the patient's history and current signs and symptoms. To support the diagnosis of otitis media, diagnostic equipment such as a pneumatic otoscope, tympanometry, and acoustic reflectometry are provided. When compared to plain otoscopy, pneumatic otoscopy is the most accurate and has greater sensitivity and specificity, while tympanometry and other techniques can help with diagnosis if pneumatic otoscopy is not accessible.

Antibiotic treatment for otitis media is debatable and necessarily related to the subtype of otitis media. Suppurative material from the middle ear can spread to nearby anatomical regions, causing consequences such as tympanic membrane perforation, mastoiditis, labyrinthitis, petrositis, meningitis, cerebral abscesses, hearing problems, lateral and cavernous sinus thrombosis, and more. As a result, particular recommendations for the treatment of otitis media have been developed. High-dose amoxicillin is the backbone of treatment in the United States for children with a proven confirmation of acute otitis media, and it has been found to be most beneficial in kids under the age of two. In countries such as The Netherlands, the treatment plan is watchful waiting, and if the problem persists, antibiotics are prescribed. Nevertheless, due to the risk of persistent middle ear effusion and its influence on hearing and speech, as well as the dangers of complications, the idea of cautious watching has not received complete acceptance in the United States and other nations. In individuals with otitis media, painkillers such as non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs like acetaminophen can be administered alone or in conjunction to produce effective pain relief.