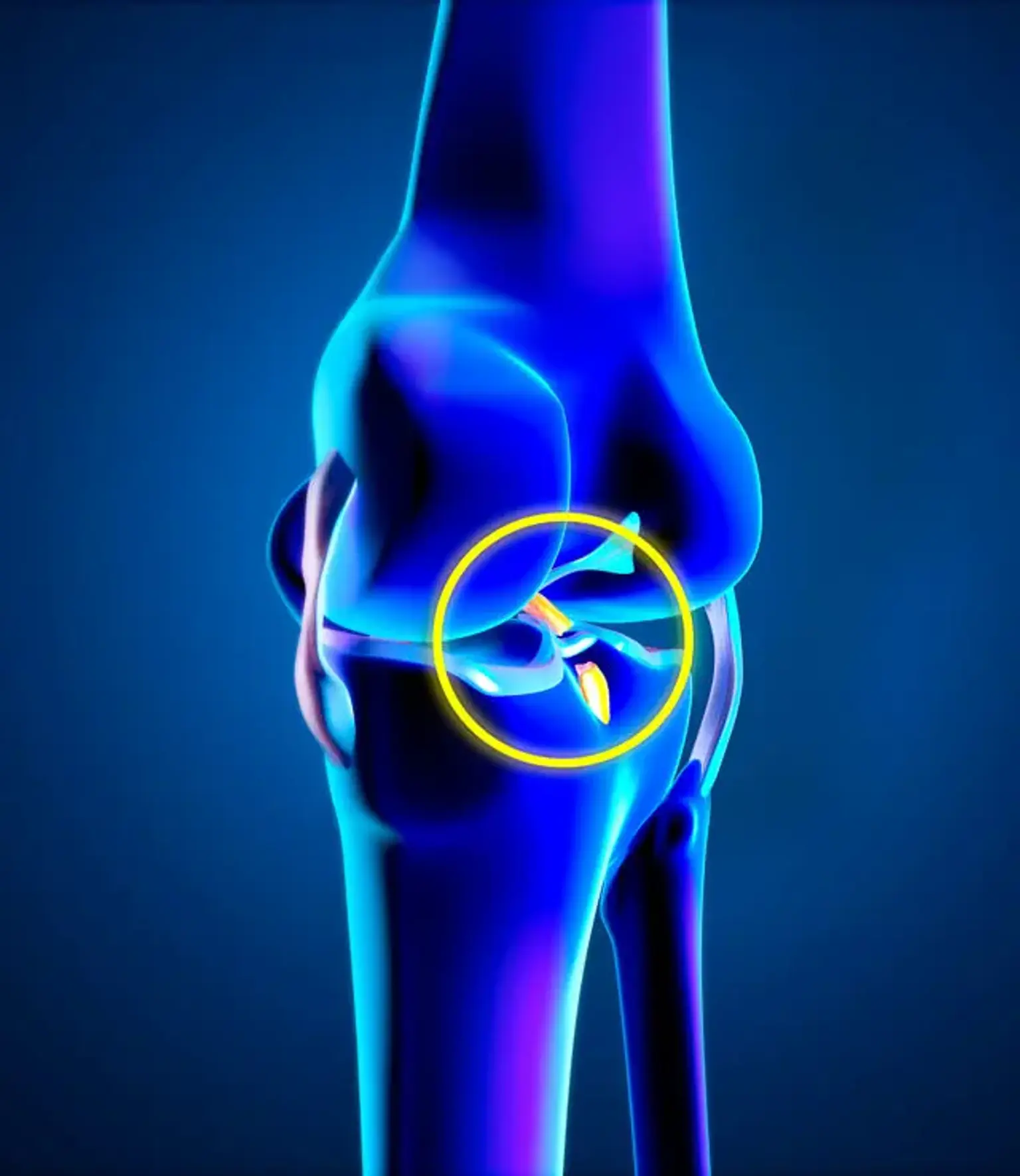

Anterior/Posterior Cruciate Ligaments

Overview

The anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) is one of two cruciate ligaments in the human knee (the other being the posterior cruciate ligament). Because they are crossed, the two ligaments are also known as "cruciform" ligaments.

Because of its anatomical position in the quadruped stifle joint (analogous to the knee), it is also known as the cranial cruciate ligament. The word cruciate means "cross." The ACL crosses the posterior cruciate ligament to form a "X," hence the name. It is made of a strong, fibrous material that aids in the control of excessive motion. This is accomplished by restricting joint mobility.

The anterior cruciate ligament is one of the four major ligaments of the knee, accounting for 85 percent of the restraining force against anterior tibial displacement between 30 and 90 degrees of knee flexion. The ACL is the most commonly injured of the four ligaments found in the knee.