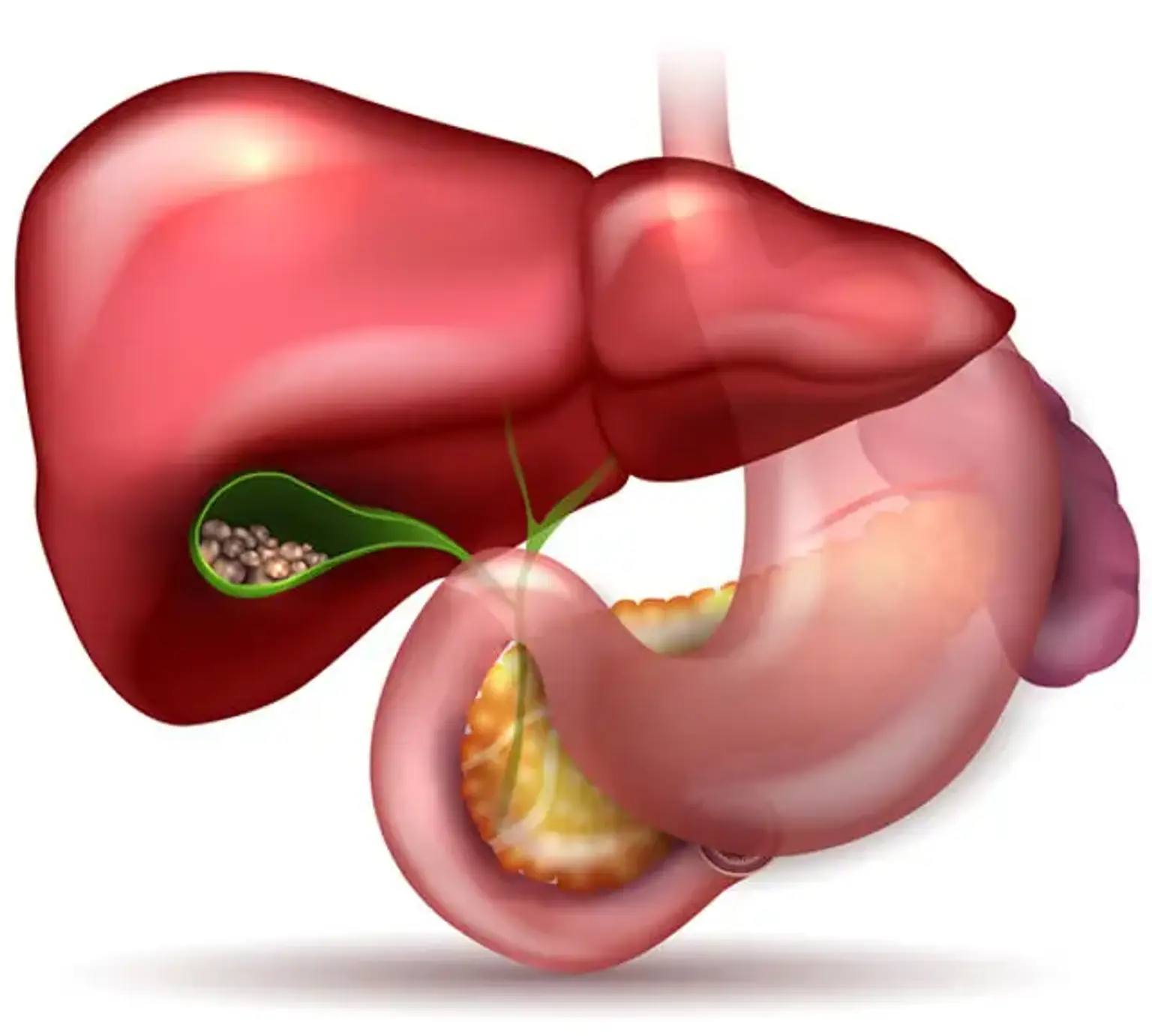

Biliary system disease

Overview

The biliary system is affected by a wide range of disorders, many of which show with similar clinical signs and symptoms. Gallstones, acute calculus cholecystitis, acute acalculus cholecystitis, Mirizzi syndrome, chronic cholecystitis, cholangitis (recurrent pyogenic, primary sclerosing, primary biliary, autoimmune), biliary tract cancers, biliary tract cysts, and other disorders are examples of these conditions.