Congenital tracheal stenosis

Overview

Congenital tracheal stenosis (CTS) occurs in roughly 1 in 64,500 instances and manifests as stridor or respiratory insufficiency in the neonatal period or infancy. The prognosis and progress of this lesion set are determined by the degree of the stenosis and concomitant diagnoses. Some children require intubation and mechanical breathing for rescue, although extracorporeal support is rarely necessary.

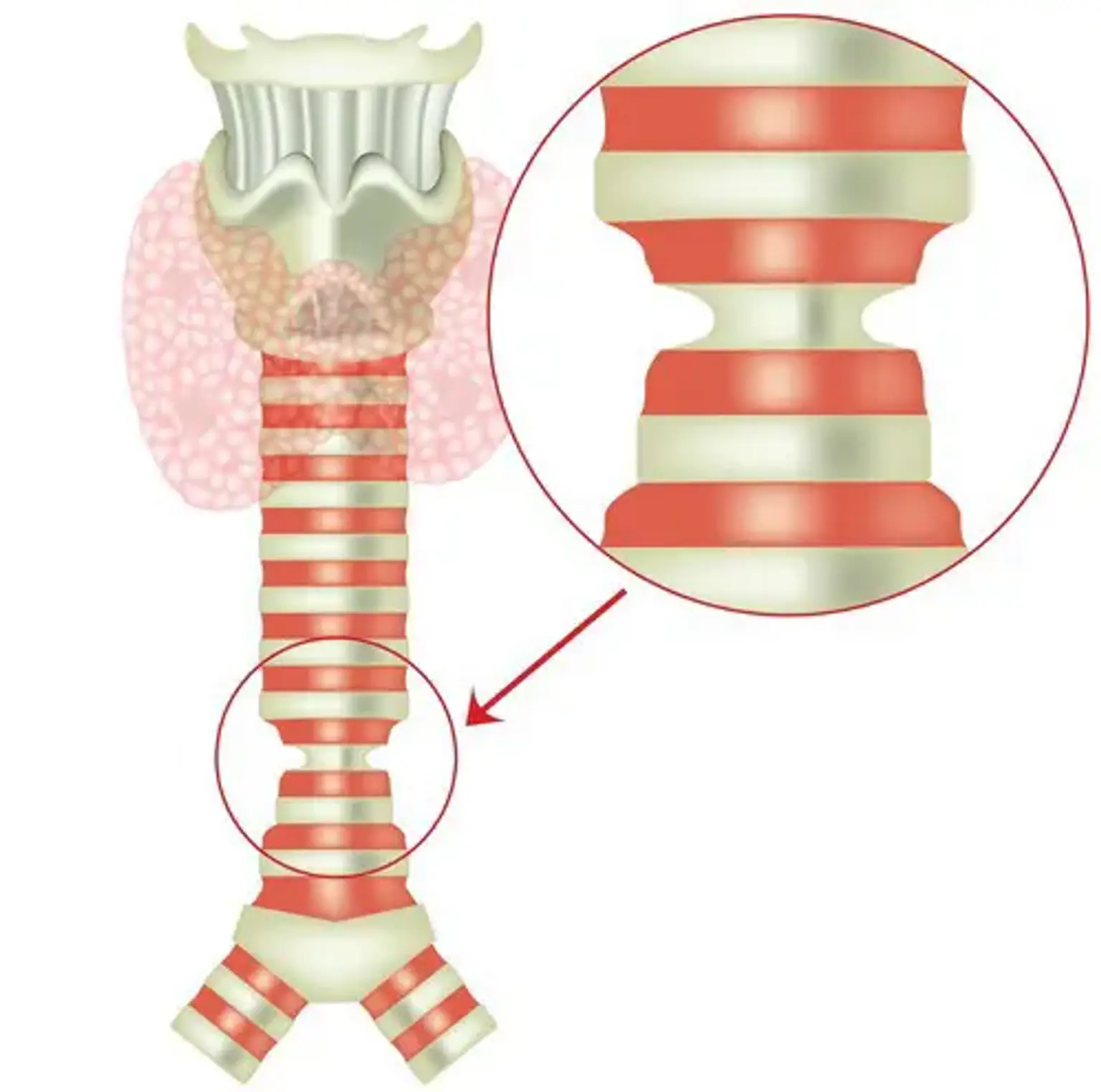

CTS is frequently caused by entire tracheal rings, which occur when the posterior membranous trachea is missing and replaced by complete circular cartilaginous rings. Tracheal involvement with such rings might be of either short or extended duration. Because this lesion is mechanical in character, medical treatment is frequently ineffective and is linked with a poor long-term prognosis. Surgical correction is still the basis of treatment.