Craniopharyngioma

Overview

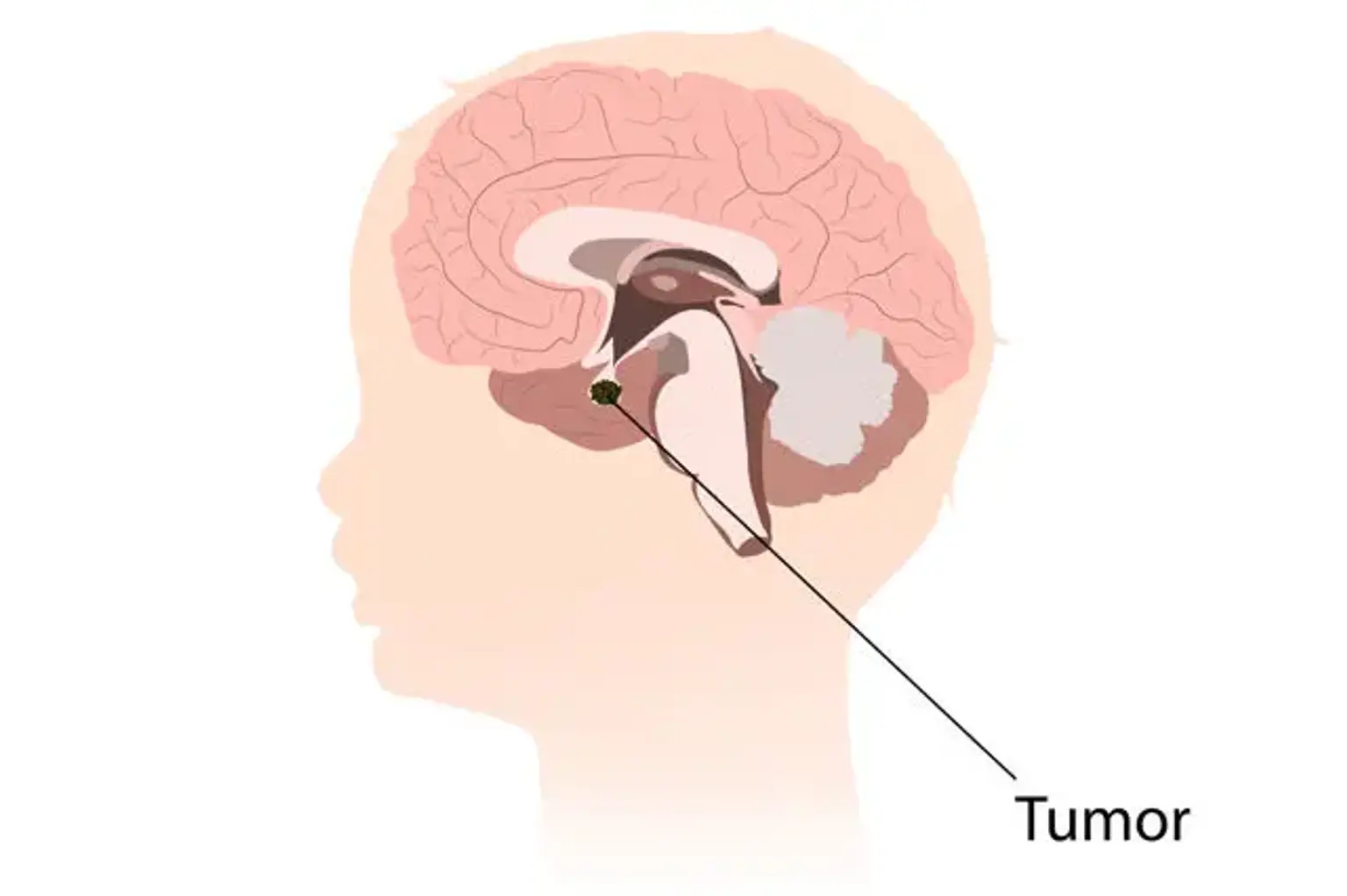

Craniopharyngioma is an uncommon, but harmless central nervous system tumor (CNS). It is a partially cystic embryonic abnormality that can arise in the sellar/parasellar area and cause a variety of symptoms including headaches, nausea and vomiting, visual problems, and endocrine disorders.

It poses a unique difficulty to the physicians who treat it, which often include neurosurgery, neuro-ophthalmology, neurology, endocrinology, and pediatrics. The difficulty stems from the tumor's capacity to attach to the surfaces around it. As a result, it is incredibly difficult to manage, and it is also infamous for its high recurrence rates.

Following histological evaluation of a surgical specimen, a definitive diagnosis is obtained. Endocrine disruptions are usually persistent and need cautious restoration. Overall, there is an 80% 5-year survival rate, albeit this is coupled with significant morbidity