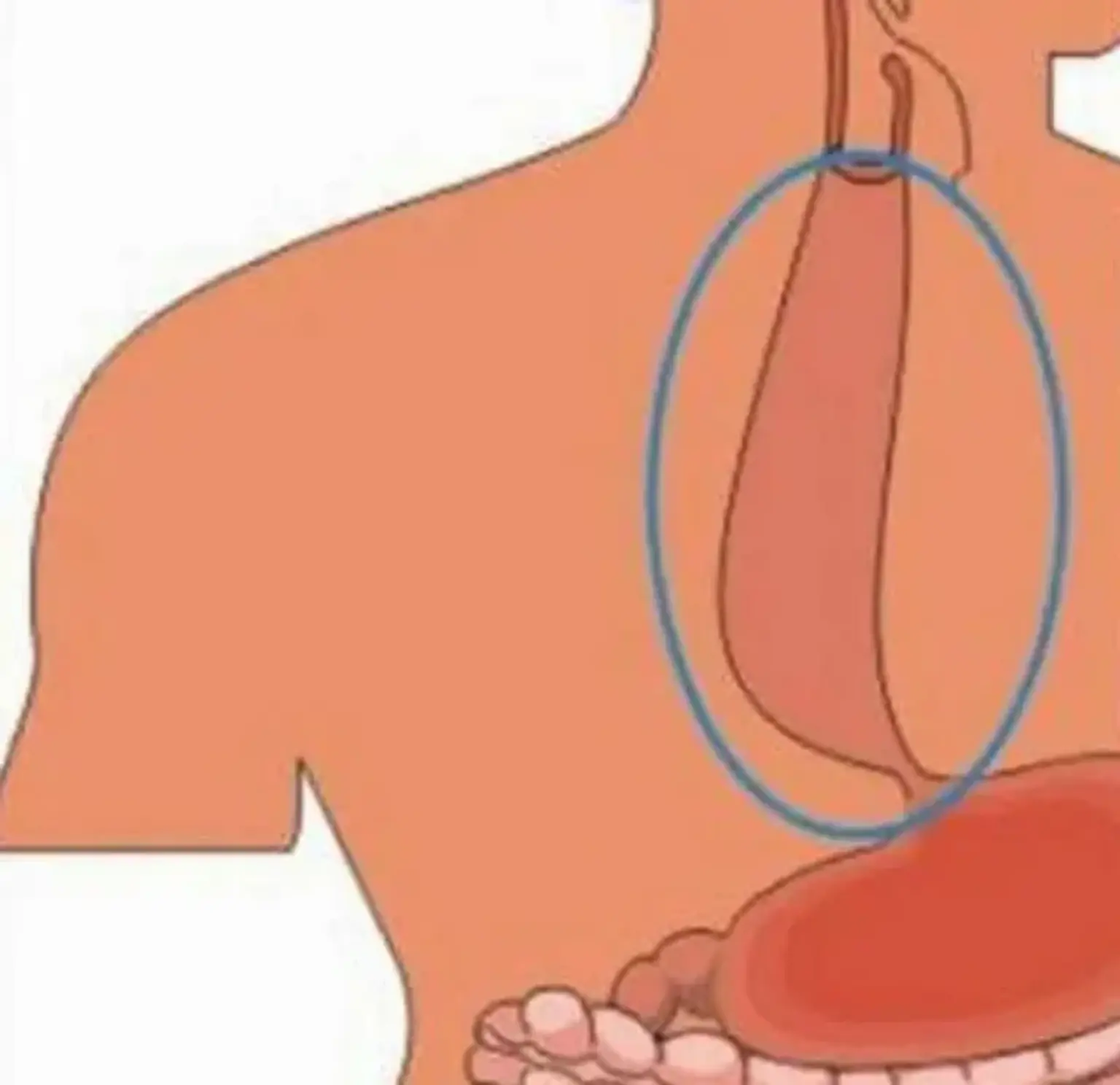

Esophageal achalasia

Overview

Esophageal achalasia is a primary esophageal motility condition of unknown origin that is defined by a lack of peristalsis and a partial or absent relaxation of the lower esophageal sphincter in response to swallowing. In institutions with a multidisciplinary approach, treatment should be personalized to the individual patient. For individuals who have failed previous treatment measures, esophageal resection should be considered as a last option.