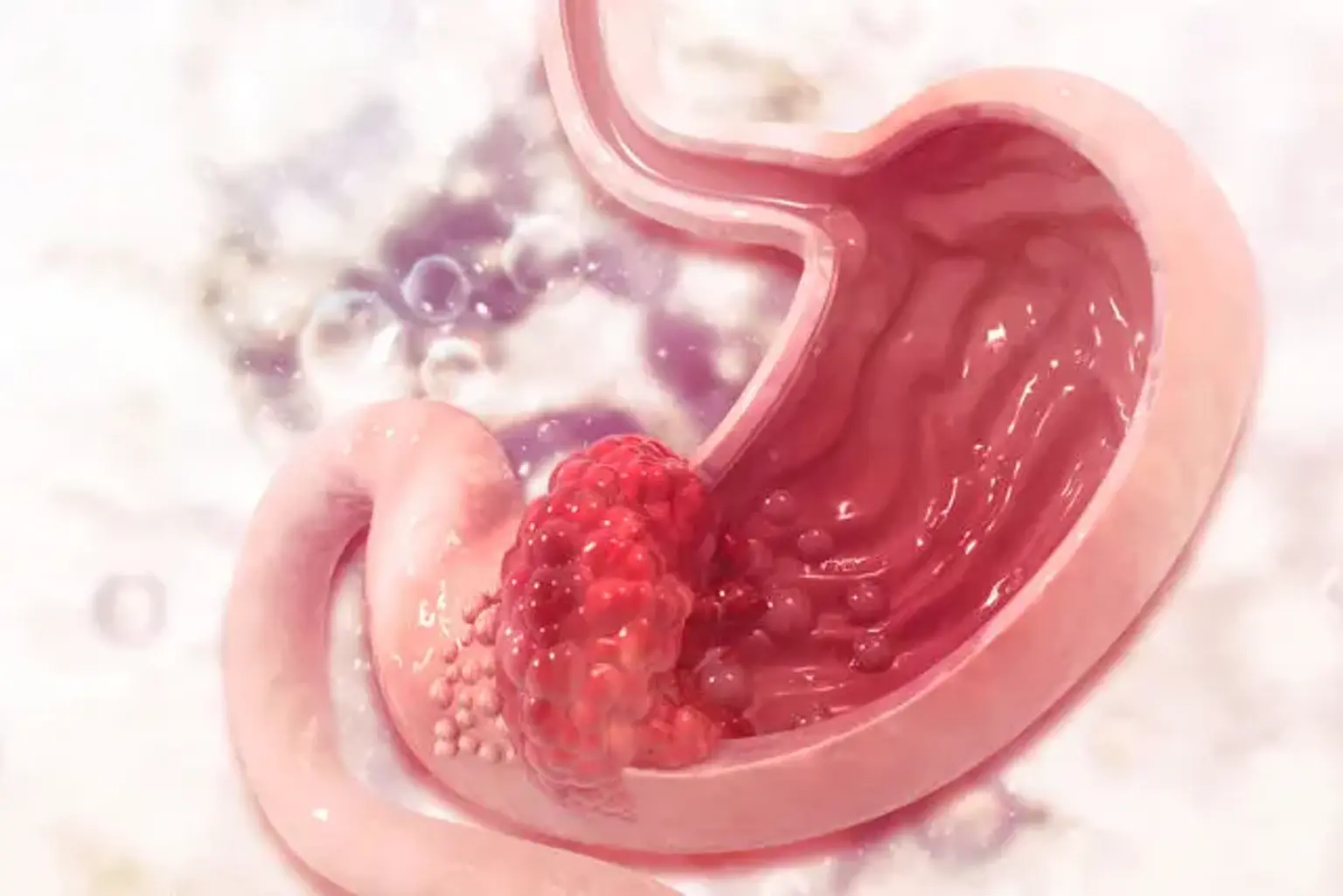

Gastric cancer

Overview

Gastric cancer is the fifth most common cancer and the third main cause of cancer deaths globally, despite a global drop since the mid-century. In the United States, the incidence of stomach cancer has dropped during the last several decades, whereas the incidence of gastroesophageal cancer has climbed.

Gastric adenocarcinoma is classified into two types: intestinal (well-differentiated) and diffuse (undifferentiated), each with its own morphologic appearance, etiology, and genetic profile. Surgical resection with appropriate lymphadenectomy is the only possibly curative therapy option for people with stomach cancer.

Perioperative therapy to enhance a patient's survival are supported by current research. Regrettably, patients with incurable, locally advanced, or metastatic illness may only be provided life-prolonging palliative care.