hidronefrosis

El hidrouréter y la hidronefrosis son afecciones comunes que se observan en las clínicas de atención primaria, medicina de emergencia y nefrología y urología. La hidronefrosis es una afección en la que el sistema colector renal de uno o ambos riñones se dilata y distiende debido a un bloqueo del flujo urinario distal a la pelvis renal (es decir, uréter, vejiga urinaria y uretra). Hidrouréter se refiere a la dilatación del uréter causada por un bloqueo en el flujo urinario.

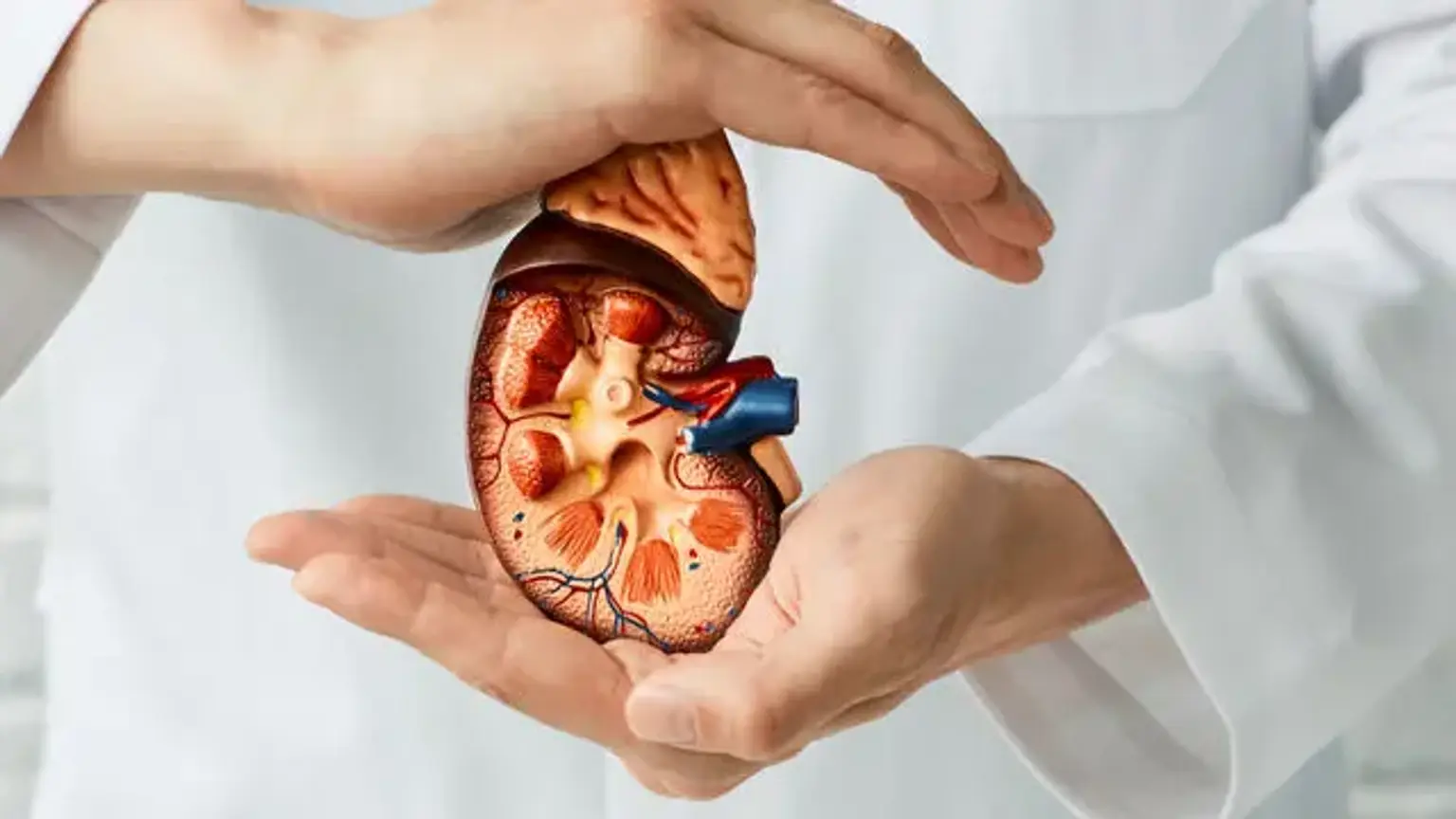

El sistema urinario es un sistema de órganos complejo y de múltiples componentes cuya función principal es mantener la homeostasis corporal mediante la regulación del volumen de líquidos corporales, el equilibrio electrolítico y la excreción de productos metabólicos finales a través de la orina. Comprende anatómicamente los riñones, los uréteres, la vejiga urinaria y la uretra. Cada riñón tiene una corteza externa y una médula interna, que se combinan para producir pirámides renales que se extienden hasta la pelvis renal, donde continúa el uréter. La hidronefrosis y el hidrouréter pueden ocurrir solos o juntos. Afectan a personas de todas las edades. Aguda o crónica, fisiológica (particularmente frecuente en mujeres embarazadas) o patológica, unilateral o bilateral, la apariencia puede ser aguda o crónica.