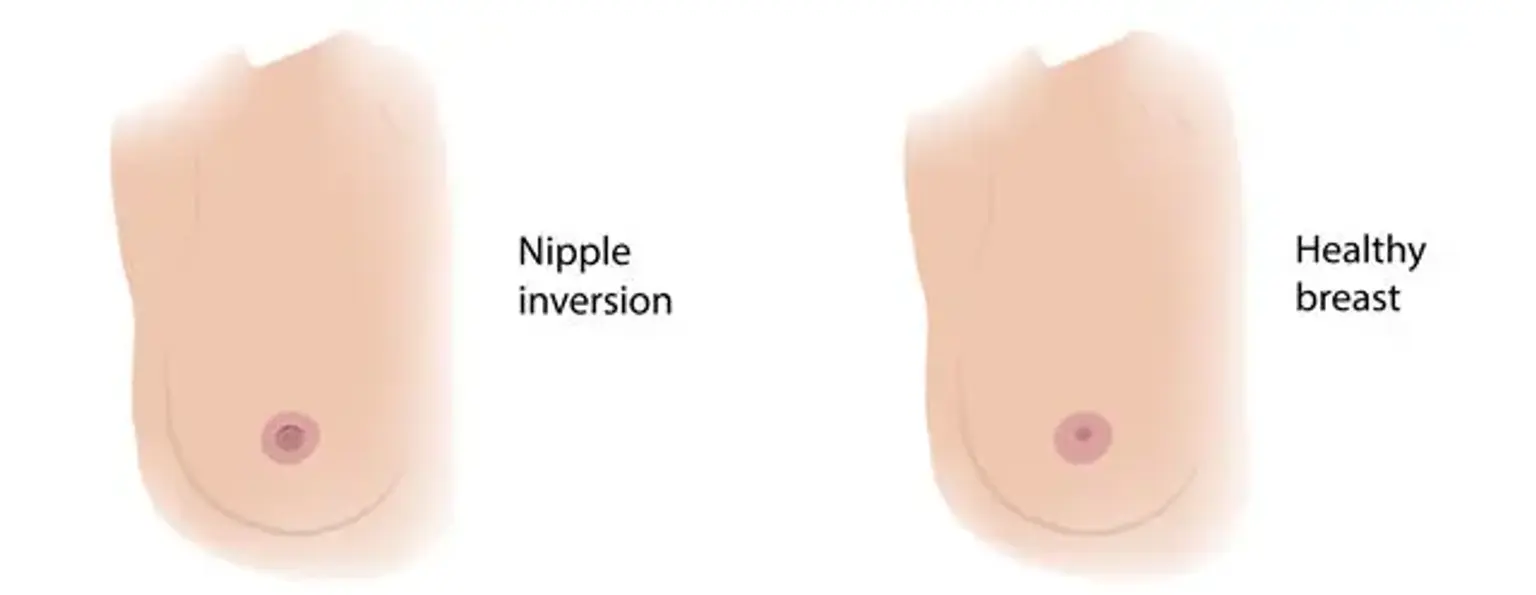

Inverted Nipple

An inverted nipple is a situation in which the nipple is curled inwards instead of projecting outwards as it should be in normal anatomy. It can affect both men and women, and it can be present at birth (congenital) or acquired during life. In contrast to the usual anatomic posture, where the inverted nipple projects beyond the line of the areolar breast, the protrusion of the inverted nipple falls beneath the areolar plane. The appearance can be distressing emotionally, as well as a concern during breastfeeding in nursing mothers. As many as 12 to 19 percent of females are born with one or more inverted nipples, which are often asymptomatic until they are nursing. The appearance might be unattractive and concerning from an aesthetic standpoint. It's important to distinguish between a benign inverted nipple and primary breast cancer.

Inverted Nipple Epidemiology

Up to ten percent of the population has a congenital nipple inversion. Both men and women are affected. Bilateral diseases account for 87 percent of cases, while family diseases account for 50 percent.