Laminectomy

Overview

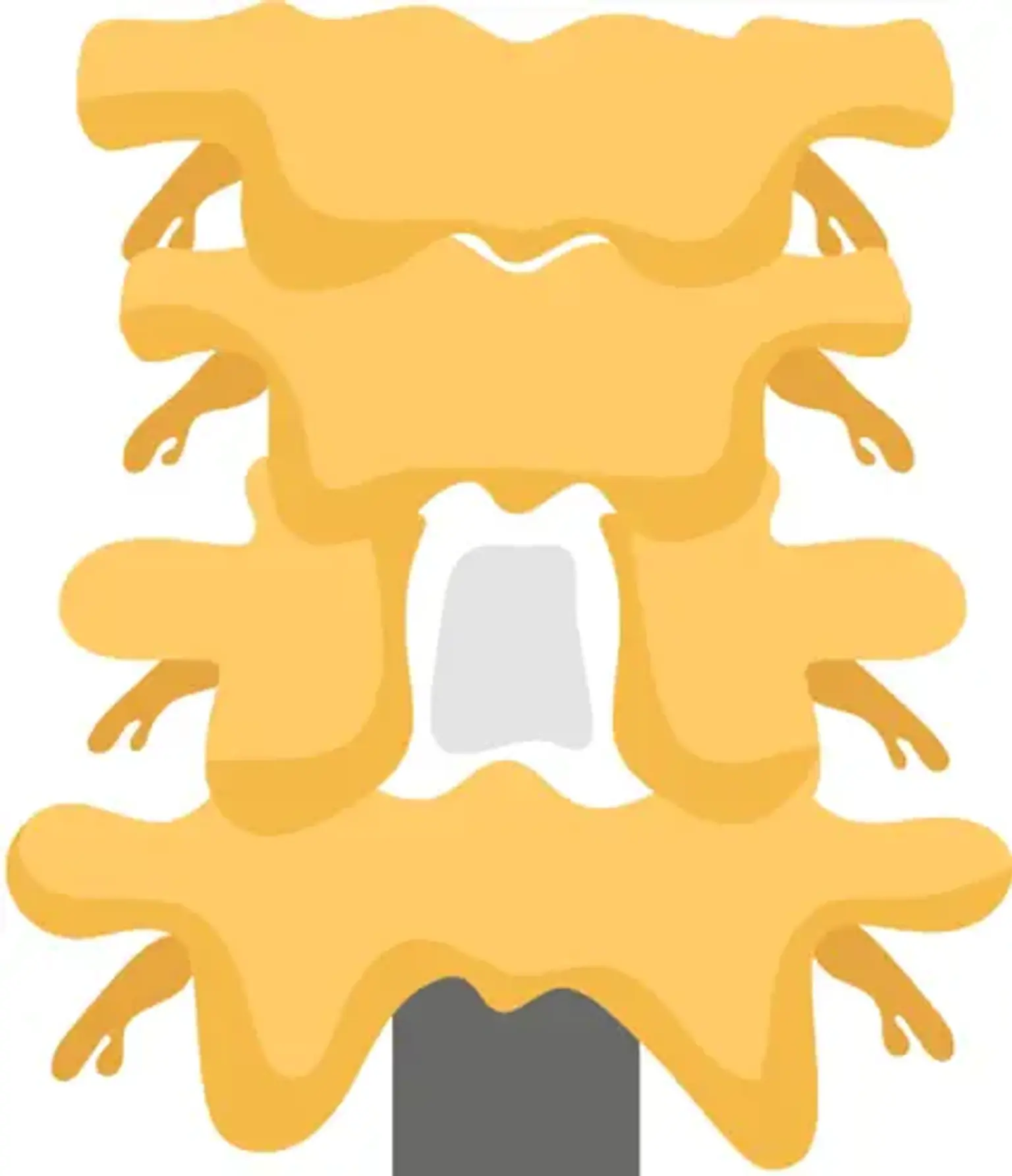

Laminectomy is one of the most popular treatments used to decompress the spinal canal in situations of restriction caused by degenerative stenosis, fracture, primary and secondary spinal tumors, abscess, and deformity. The removal of the spinous process and lamina is confined laterally to the medial region of the facet joints. For optimal clinical recovery and the avoidance of failed back surgery syndrome, the central canal, lateral recesses, and neural foramina must be decompressed.