Laparoscopic Cholecystectomy

What is laparoscopic cholecystectomy?

A cholecystectomy is a surgical procedure that removes your gallbladder, which is a pear-shaped organ located on the upper right side of your belly directly below your liver. The gallbladder collects and stores bile, which is a digestive fluid generated by the liver.

Laparoscopic cholecystectomy is a standard surgical procedure with a low risk of complications. You may usually go home the same day as your cholecystectomy. An open cholecystectomy is more intrusive than a laparoscopic cholecystectomy. This method of gallbladder removal requires a bigger incision.

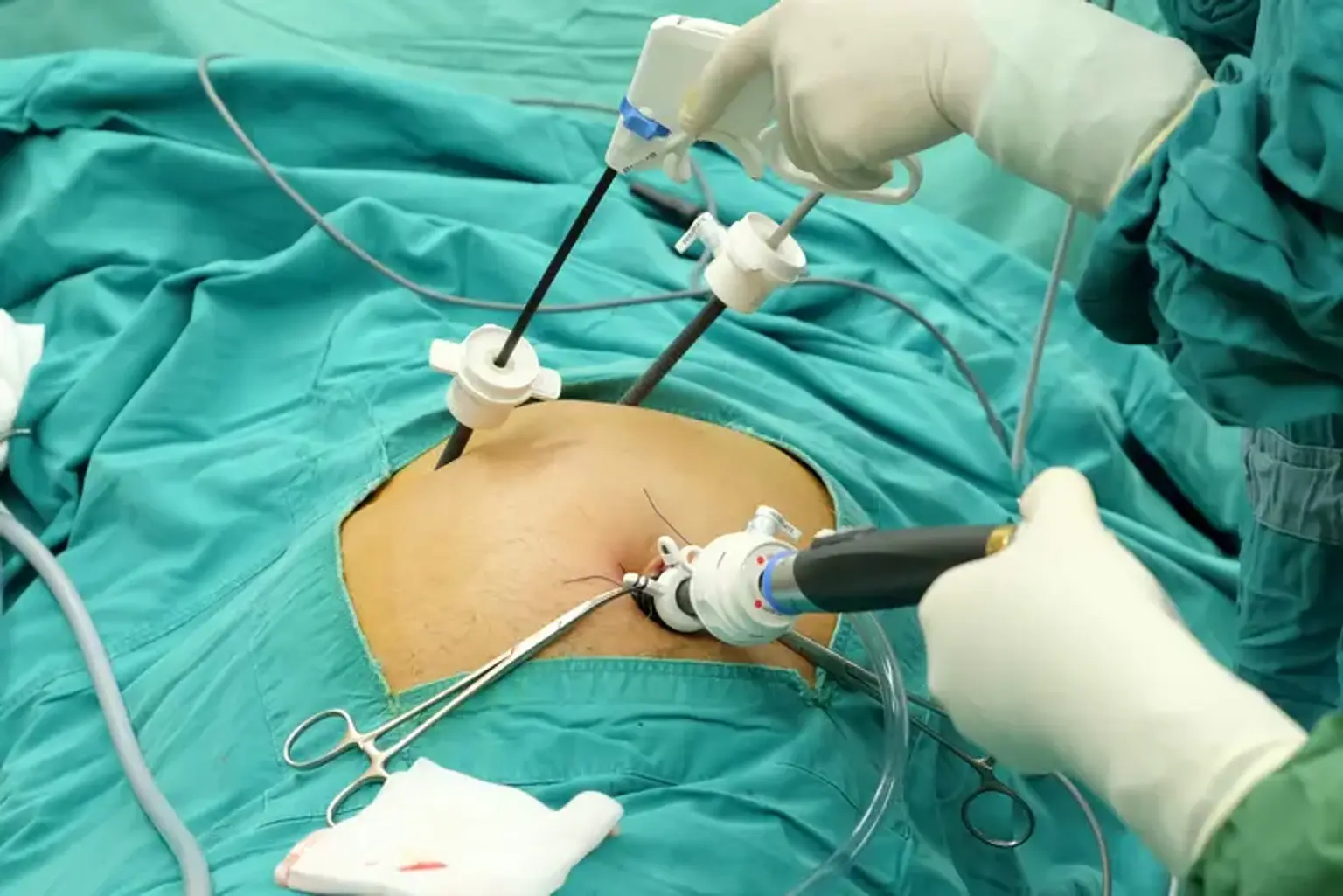

A laparoscopic cholecystectomy is gallbladder removal operation. On the right side of your abdomen, the surgeon makes a few tiny incisions (belly). A laparoscope, a narrow tube with a camera on the end, is inserted through one incision by the surgeon. A screen displays your gallbladder. The gallbladder is subsequently removed through another tiny incision.