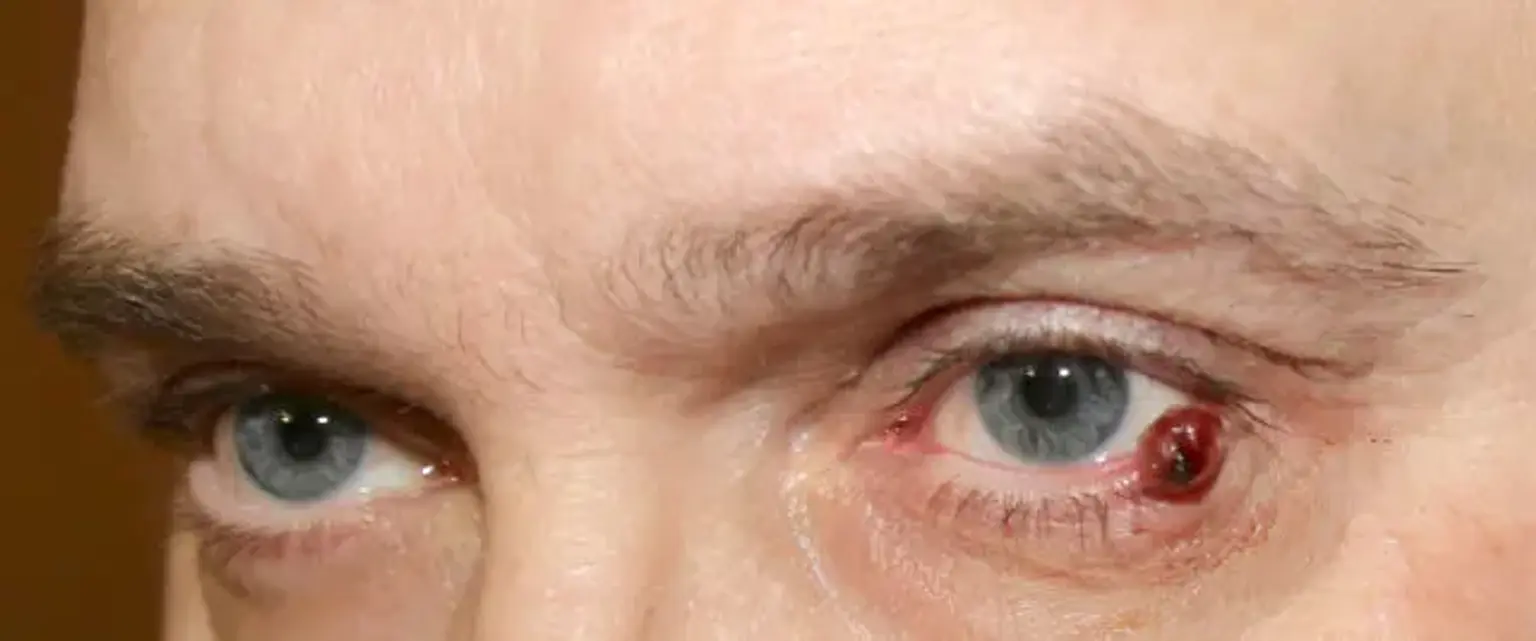

Lymphangioma

Vascular malformations are inborn developmental abnormalities of the blood vessels that are evident at birth and are divided into low flow lesions (capillary, venous, and lymphatic anomalies) and rapid flow lesions (arterial and arterio-venous congenital anomalies) based on the flow pattern. Lymphangiomas, also known as lymphatic malformations, are benign hamartomas that originate abnormally from the primitive lymphatic sacs. They account for 25 percent of benign vascular masses in children and 4 percent of vascular masses. Lymphangiomas present as smooth, homogeneous, nontender, collapsible, solitary masses that can be transilluminated in any part of the body, with 75 percent of the time appearing in the head and neck region, 15 percent in the axilla, and the rest in the thoracic and abdominal regions. Lymphangiomas are evident at birth in 50-60% of patients, and they become visible in 80-91 percent of cases during adolescence and adulthood. Lymphangiomas are made up of dilated lymph vessels filled with proteinaceous material that is normally not related to the lymphatic system. The great majority of lymphangiomas are congenital, although they can also develop as a result of trauma, inflammatory process, or lymphatic blockage in rare situations.

Epidemiology

Vascular malformations are vascular defects that occur during development. In the United States, lymphangiomas are uncommon. They account for 4.2% of all vascular tumors in children and 26% of all benign pediatric vascular masses. There is no preference based on race or gender. Lymphangiomas usually appear at birth or within the first few years of life, but cutaneous lymphangioma circumscriptum is more common in adults.