Overview

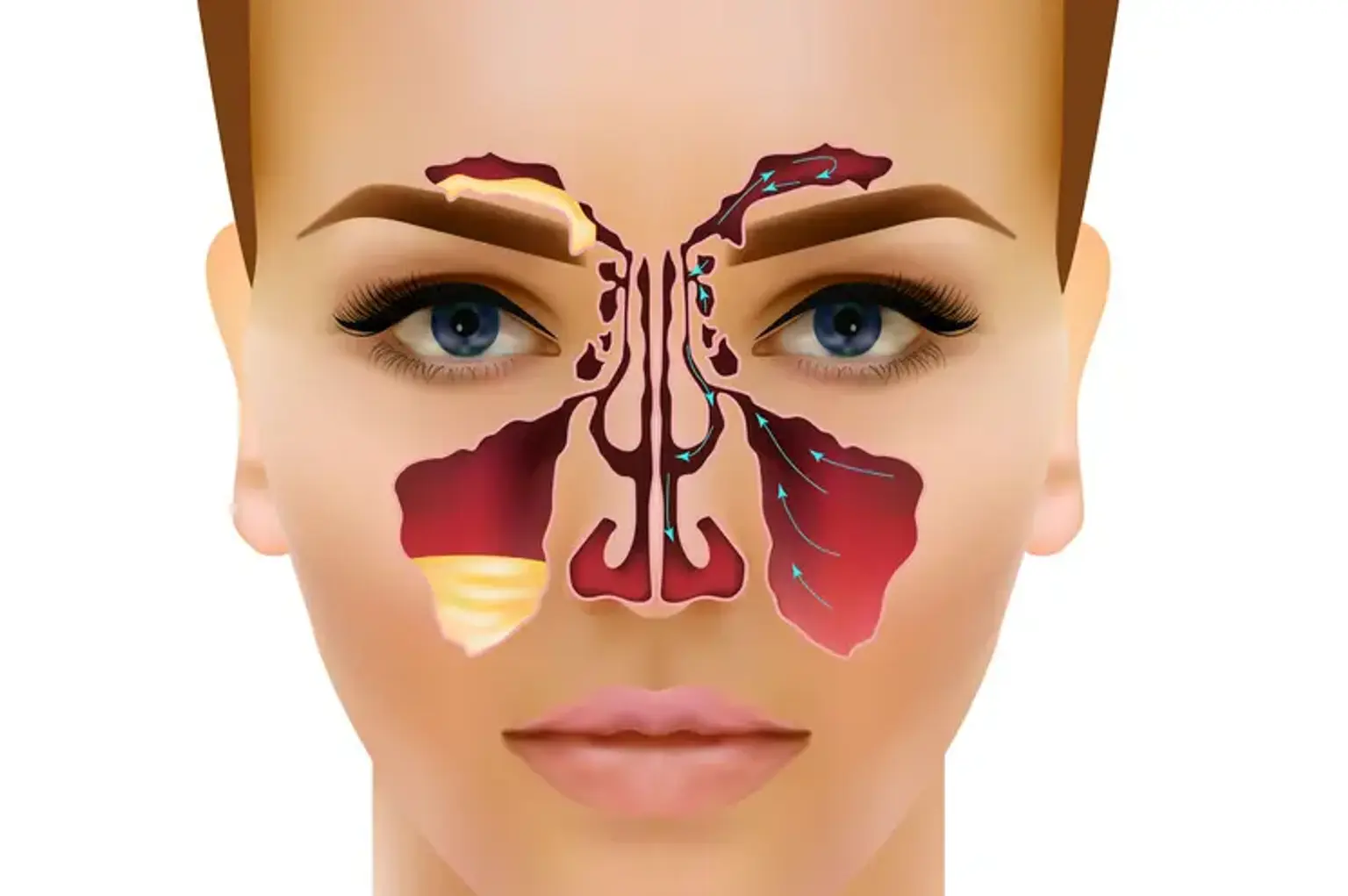

The maxillary sinuses are the largest of the paranasal sinuses, located behind the cheekbones on either side of the nose. They play a crucial role in the respiratory system, helping to filter and humidify the air we breathe. These sinuses also help reduce the weight of the skull and enhance the resonance of our voice. When the maxillary sinuses become blocked or inflamed, it can cause discomfort, pressure, and even facial deformities, making proper care and treatment essential for maintaining both health and appearance.

The importance of treating maxillary sinus issues goes beyond just alleviating pain. Conditions like infections, cysts, and volume loss can lead to chronic issues that affect a person's overall well-being and facial aesthetics. Treating these problems promptly can restore not only sinus health but also contribute to better quality of life and improved facial appearance.

What is Maxillary Sinus Treatment?

Maxillary sinus treatment refers to the procedures used to address a variety of issues that can affect the maxillary sinuses, such as infections, cysts, inflammation, and volume loss. These treatments can range from non-invasive options like medications and nasal sprays to more advanced procedures like surgery and volume restoration techniques.

One of the main goals of maxillary sinus treatment is to relieve symptoms such as pain, sinus pressure, and congestion. These symptoms often result from infections or inflammation that prevent the sinuses from draining properly. When these conditions become chronic, surgical intervention may be needed to correct blockages or restore lost sinus volume. Restoration of sinus volume is especially important for individuals experiencing facial sagging or asymmetry caused by the loss of soft tissue support around the sinuses.

In addition to medical benefits, many patients seek maxillary sinus treatment for cosmetic reasons. Treatments aimed at restoring the structure and volume of the sinuses can also improve facial appearance by lifting the cheek area and reducing the appearance of hollow or sunken cheeks.