Onychomycosis

Overview

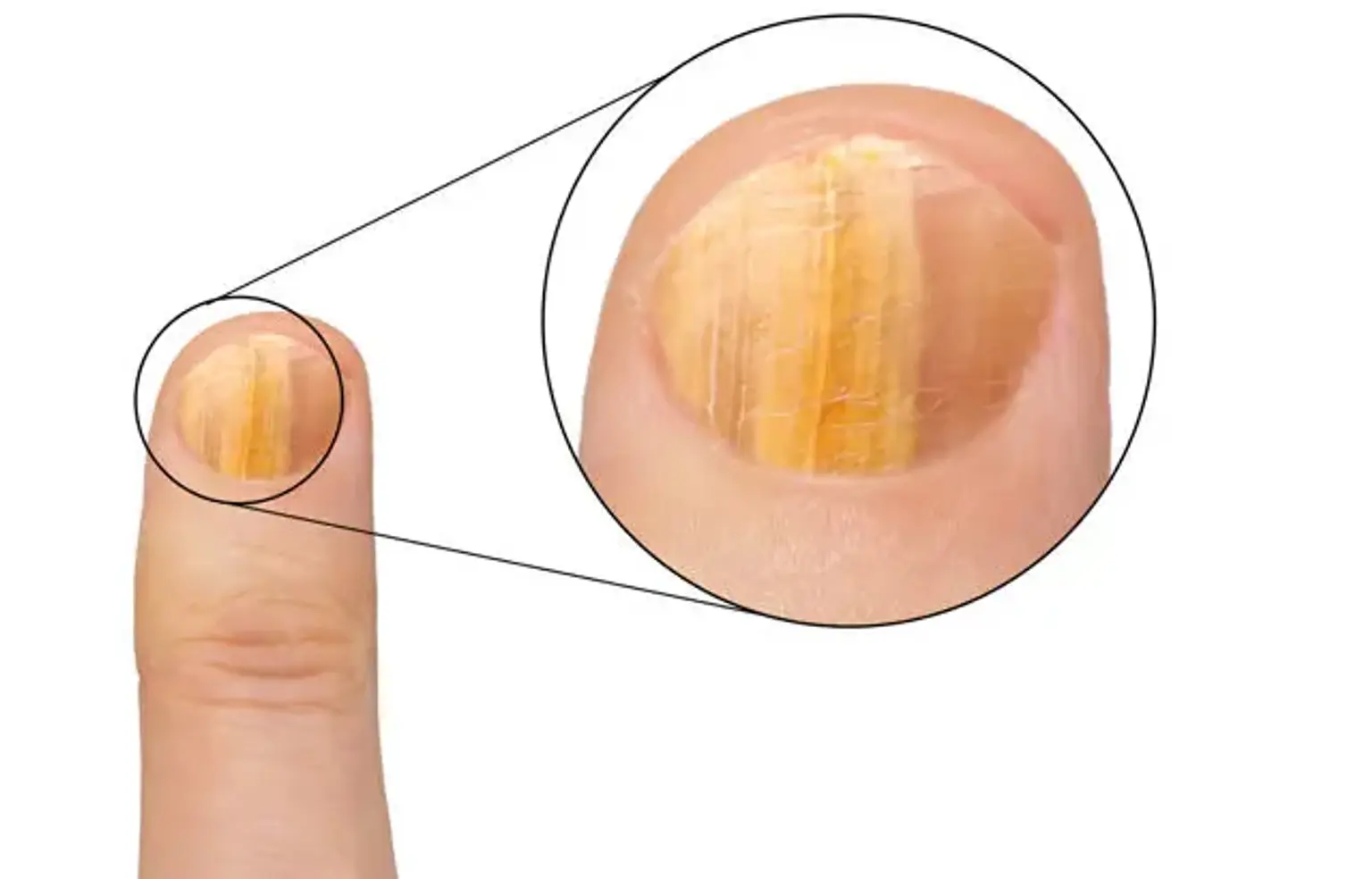

The most prevalent nail infective condition is onychomycosis. It is mostly caused by anthropophilic dermatophytes, specifically Trichophyton rubrum. The second cause of onychomycosis is caused by yeasts such as Candida albicans and Candida parapsilosis, as well as molds such as Aspergillus spp.

Mycology should corroborate the clinical suspicion of onychomycosis. Onychoscopy is a novel technology that can assist the clinician since it displays a characteristic fringed proximal border in onychomycosis. Treatment is determined by the mode of nail invasion, the fungus type, and the quantity of infected nails.

Oral therapies are frequently hampered by medication interactions, and topical antifungal lacquers are less effective. A mix of oral and systemic medication is frequently the best option.