Osgood-Schlatter disease (OSD)

Overview

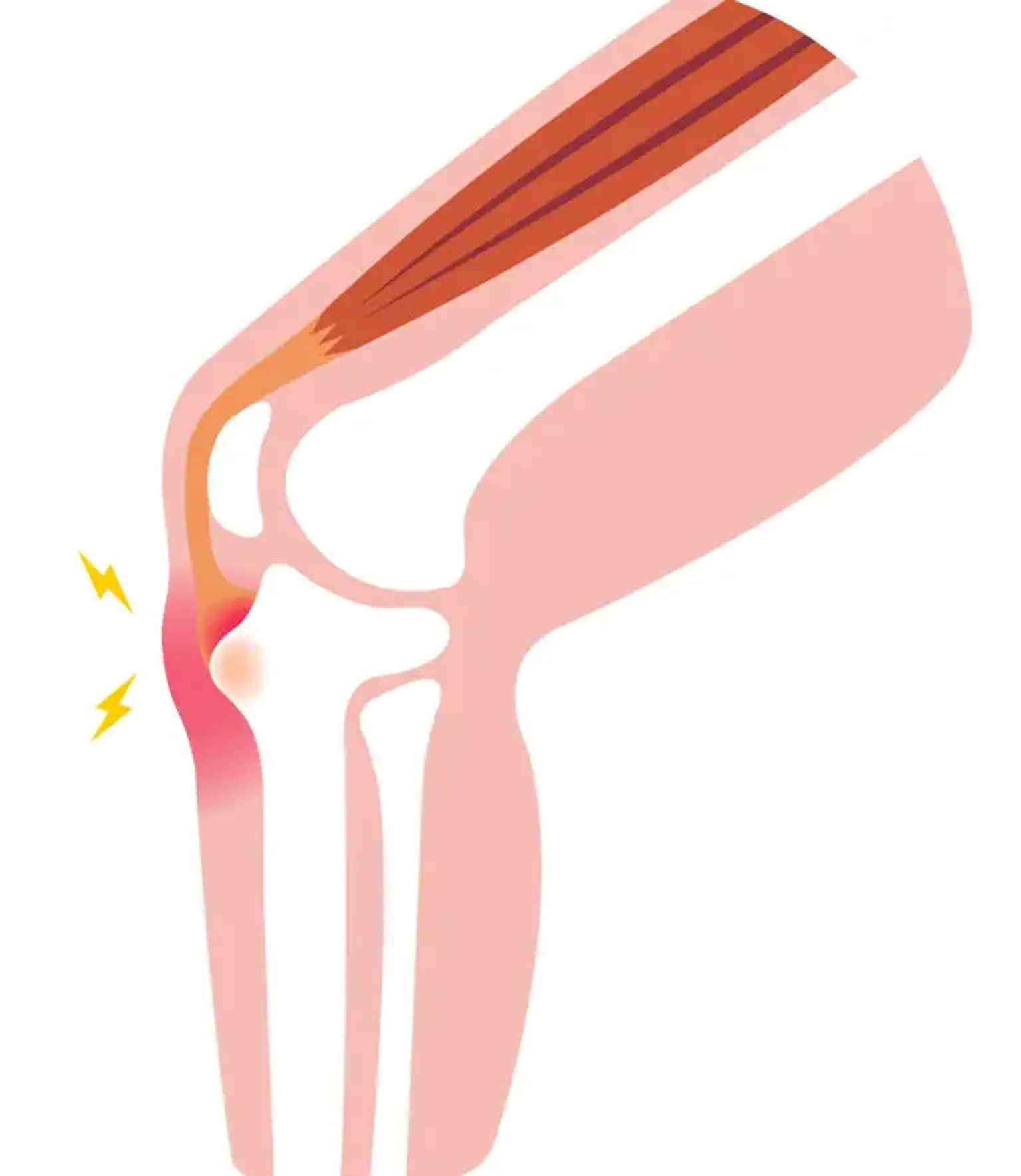

Osgood Schlatter disease, also known as osteochondrosis, tibial tubercle apophysitis, or tibial tubercle traction apophysitis, is a prevalent cause of anterior knee discomfort in the skeletally immature athletic population. Tenderness at the patellar tendon insertion point at the tibial tuberosity is traditionally associated with atraumatic, gradual start of anterior knee discomfort.

The syndrome is self-limiting and develops as a result of recurrent extensor mechanism stress activities like leaping and sprinting. Overall treatment is determined by the level of pain, and management includes symptomatic treatment with ice and NSAIDs, as well as activity modification and relative rest from inciting activities in conjunction with a lower extremities stretching regimen to correct underlying predisposing biomechanical factors.