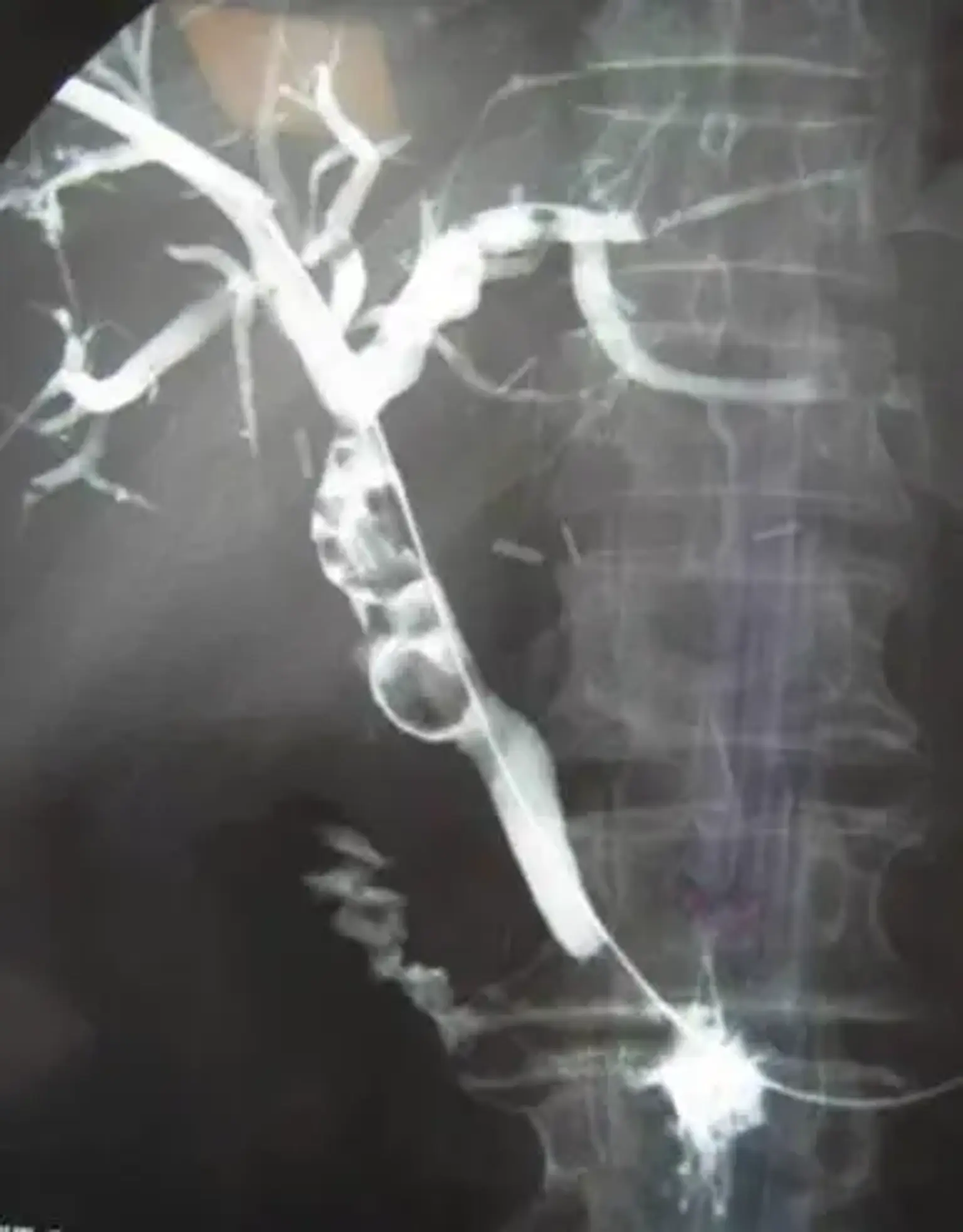

Percutaneous Transhepatic Cholangiography

Overview

Noninvasive imaging might be difficult to evaluate patients with obstructive biliary pathology. Percutaneous cholangiopancreatography, in combination with endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography, is essential for diagnosing and treating particular pathologies.