Spondylolisthesis

Overview

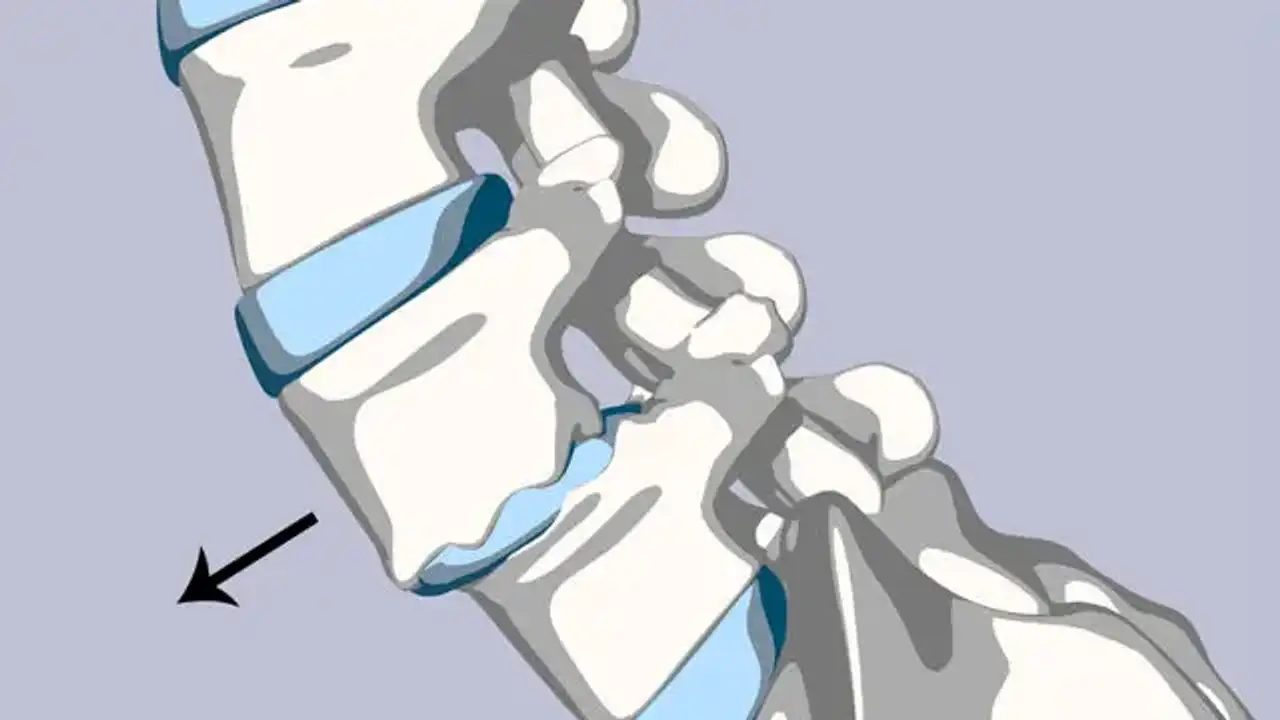

The spine is composed of 24 tiny rectangular-shaped bones called vertebrae that are placed on top of one another. These bones join together to form a canal that protects the spinal cord.

Spondylolisthesis is a spinal disorder that produces discomfort in the lower back. It happens when one of your vertebrae, or spine bones, slides out of position and lands on the vertebra below it. Nonsurgical treatment can usually ease your problems. In most situations, surgery for severe spondylolisthesis is effective.

Spondylolisthesis definition

A posterior defect in the vertebral body at the pars interarticularis is referred to as spondylolysis. This deformity is usually caused by trauma or chronic repeated loading and hyperextension. Spondylolisthesis occurs when this instability causes the vertebral body to translocate.

This defect necessitates a fracture or distortion of the posterior spine components, resulting in pars elongation. This disorder affects people of all ages, with the underlying cause differing depending on the age range.

Epidemiology

Spondylolisthesis is most usually found in the lower lumbar spine, but it can also occur in the cervical spine and, in rare cases, the thoracic spine (unless in cases of trauma). Degenerative spondylolisthesis mostly affects adults and is more frequent in women than men, with an elevated risk in the obese. Isthmic spondylolisthesis is more frequent in adolescence and young adulthood, but it may go unnoticed until symptoms appear in maturity.

Males have a greater frequency of isthmic spondylolisthesis. Dysplastic spondylolisthesis is more frequent in children, with girls being more afflicted than men. Current prevalence estimates range from 6 to 7 percent for isthmic spondylolisthesis by the age of 18 years, and up to 18 percent for adult patients receiving lumbar spine MRI.

75 percent of all instances of spondylolisthesis are grade I. Spondylolisthesis most typically occurs at the L5-S1 level, with the L5 vertebral body anteriorly translating onto the S1 vertebral body. Spondylolisthesis is most commonly seen at the L4-5 level.

Etiology

Spondylolisthesis is often classified as having one of five etiologies: degenerative, isthmic, traumatic, dysplastic, or pathologic. Degenerative spondylolisthesis is caused by degenerative alterations in the spine and does not include a deficiency in the pars interarticularis. It is frequently caused by a combination of facet joint and disc degeneration, which causes instability and forward movement of one vertebral body relative to the neighboring vertebral body.

Isthmic spondylolisthesis is caused by pars interarticularis deficiencies. The origin of isthmic spondylolisthesis is unknown, however a likely etiology includes adolescent microtrauma from activities such as wrestling, football, and gymnastics, which involve frequent lumbar extension.

Traumatic spondylolisthesis is more frequent after fractures of the pars interarticularis or the facet joint structure. Dysplastic spondylolisthesis is a congenital condition caused by a change in the orientation of the facet joints, resulting in an aberrant alignment.

The facet joints in dysplastic spondylolisthesis are more sagittally orientated than the conventional coronal orientation. Pathologic spondylolisthesis can be caused by a systemic source, such as bone or connective tissue problems, or by a localized process, such as infection, malignancy, or iatrogenic cause. A first-degree relative with spondylolisthesis, scoliosis, or occult spina bifida at the S1 level is another risk factor for spondylolisthesis.

Pathophysiology

Spondylolisthesis can arise as a result of any process that weakens the supports that maintain the vertebral bodies aligned. Local discomfort from mechanical motion or radicular or myelopathic pain from compression of the exiting nerve roots or spinal cord might develop as one vertebra moves relative to the surrounding vertebrae. When children reach puberty, their spondylolisthesis grade is more likely to worsen. Patients over the age of 65 who have lower grade I or II spondylolistheses are less likely to evolve to higher grades over time.

Types of spondylolisthesis

Types of spondylolisthesis include:

- Congenital spondylolisthesis occurs when a baby’s spine doesn’t form the way it should before birth. The misaligned vertebrae put the person at risk for slippage later in life.

- Isthmic spondylolisthesis happens as a result of spondylolysis. The crack or fracture weakens the bone.

- Degenerative spondylolisthesis, the most common type, happens due to aging. Over time, the discs that cushion the vertebrae lose water. As the disks thin, they are more likely to slip out of place.

Less common types of spondylolisthesis include:

- Traumatic spondylolisthesis happens when an injury causes vertebrae to slip.

- Pathological spondylolisthesis occurs when a disease — such as osteoporosis — or tumor causes the condition.

- Post-surgical spondylolisthesis is slippage as a result of spinal surgery.

Classification

There are several categorization systems for etiology, nomenclature, spondylolysis and spondylolisthesis subtypes, and therapy.

One of the most often utilized categorization methods to describe the etiology of spondylolisthesis is the A. Wiltse Classification. It is caused by one of five primary causes: degenerative, isthmic, traumatic, dysplastic, or pathologic.

- Dysplastic spondylolisthesis (Type 1) is a congenital condition caused by a change in the orientation of the facet joints, resulting in an aberrant alignment. The facet joints in dysplastic spondylolisthesis are more sagittally orientated than the conventional coronal orientation.

- Isthmic spondylolisthesis is caused by pars interarticularis deficiencies. The origin of isthmic spondylolisthesis is unknown, however, a likely etiology includes adolescent microtrauma from activities such as wrestling, football, and gymnastics, which involve frequent lumbar extension. Type II is isthmic and is further subdivided into Type IIA and Type IIB. Type IIA is caused by a stress fracture of the pars interarticularis (spondylolysis), resulting in anterior vertebral slippage. Type II B is characterized by repeated fractures and subsequent healing, which leads in extension of the pars interarticularis and anterior vertebral slippage.

- Degenerative spondylolisthesis (Type 3) is caused by degenerative alterations in the spine and does not involve a deficiency in the pars interarticularis. It is commonly associated with coupled facet joint and disc degeneration, which results in instability and forward movement of one vertebral body relative to the neighboring vertebral body. Facet joint arthritis, which causes ligamentum flavum weakening, results in anterior vertebral slippage.

- Traumatic spondylolisthesis (Type 4) occurs most commonly following fractures of the pars interarticularis or the facet joint structure.

- Pathologic spondylolisthesis (Type 5) can be caused by a systemic cause, such as bone or connective tissue problems, or by a localized process, such as infection or tumor.

- Iatrogenic spondylolisthesis (Type 6) is a possible complication of spine surgery. These individuals will almost always have had a previous laminectomy.

Additional risk factors for spondylolisthesis include a first-degree relative with spondylolisthesis, scoliosis, or Spina Bifida at the S1 level

Clinical presentation

Patients with lumbar spondylolisthesis often experience sporadic and localized low back pain, whereas those with cervical spondylolisthesis typically experience localized neck discomfort. Flexing and stretching at the afflicted segment aggravates the pain, as this might create mechanic discomfort from motion. Direct probing of the afflicted part may aggravate pain.

Pain can also be radicular in nature because the exiting nerve roots become compressed due to the narrowing of nerve foramina as one vertebra slips on the adjacent vertebrae. The traversing nerve root (root to the level below) can also be impinged by associated lateral recess narrowing, disc protrusion, or central stenosis. Certain postures, such as resting supine, can occasionally alleviate pain.

This improvement is related to the spondylolisthesis's instability, which decreases with supine position, alleviating pressure on the bone parts and opening the spinal canal or neural foramen. Buttock discomfort, numbness or weakness in the leg(s), trouble walking, and, in rare cases, loss of bowel or bladder control are other signs of lumbar spondylolisthesis.

A stenotic canal may be shown by doing a straight leg test on a supine subject. Because hamstring contractures are frequently associated with spondylolisthesis, this test may result in localized discomfort. A complete neurologic examination is essential, as previously stated. The most common symptom of L5 radiculopathy is a weakness of ankle dorsiflexion and extension of the great toe. This deficiency may also reduce the Achilles tendon reflex. L4 radiculopathy can cause quadriceps weakness and a reduced patellar tendon response.

Physical Examination

Your child's doctor will begin by obtaining a medical history and inquiring about his or her general health and symptoms. They'll want to know if your youngster is involved in sports. Children who participate in sports that put too much strain on the lower back are more prone to develop spondylolysis or spondylolisthesis.

Your child's doctor will carefully examine your child's back and spine, looking for:

- Areas of tenderness

- Limited range of motion

- Muscle spasms

- Muscle weakness

Your child's posture and gait will also be observed by the doctor (the way they walk). Tight hamstrings can cause a patient to stand awkwardly or walk with a stiff-legged stride in some situations.

Diagnosis

Anteroposterior and lateral plain films, as well as lateral flexion-extension plain films, constitute the gold standard for spondylolisthesis diagnosis. The aberrant alignment of one vertebral body to the next, as well as probable motion with flexion and extension, would suggest instability. A pars deformity, known as the "Scotty dog collar," can occur in isthmic spondylolisthesis.

X-rays. Images of dense structures, such as bone, may be obtained using X-rays. The doctor may request X-rays of your child's lower back from various angles to search for a stress fracture and to see how the vertebrae are aligned. Spondylolysis is diagnosed when x-rays reveal a crack or stress fracture in the pars interarticularis part of the fourth or fifth lumbar vertebra.

The "Scotty dog collar" illustrates a fracture of the pars interarticularis by displaying a hyperdensity where the collar would be on the cartoon dog. For diagnosing spondylolisthesis, computed tomography (CT) of the spine has the best sensitivity and specificity. Spondylolisthesis can be shown more clearly on sagittal reconstructions than on axial CT imaging.

MRI of the spine can reveal related soft tissue and disc abnormalities, although it is more difficult to see bony detail and a probable par defect on MRI.

Scanners for Single Photo Emission Computed Tomography (SPECT). A SPECT scan detects regions of enhanced bone activity by using a little quantity of radioactive material. When CT scans are unavailable, a SPECT scan can be used to diagnose spondylolysis. However, this test is no longer widely utilized.

Scans for Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI). An MRI scan is more accurate than an X-ray in capturing pictures of the body's soft tissues. An MRI can assist your child's doctor to identify if the intervertebral disks between the vertebrae are degenerating prematurely or if a slipped vertebra is pushing on spinal nerve roots. It can also assist the clinician in determining whether or not there is damage to the pars interarticularis before an X-ray is taken.

Management

Non-surgical treatment options include modifying the activities that may have increased the pain, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), physical therapy, stretching, and, in certain cases, the use of a lumbosacral orthosis. According to a 2009 meta-analysis of spondylolysis and grade 1 spondylolisthesis, over 84 percent of teenage patients treated nonoperatively had a good clinical result after one year. This research similarly found no difference between individuals who used a brace and those who did not.

The overall effect is most likely determined by the activity limitation rather than the bracing. In addition, a six-week course of physical therapy with an emphasis on core exercise strengthening and flexibility should be undertaken. Additionally, epidural injections can provide brief pain relief, but the risk of future infection, albeit modest, is conceivable.

While most patients improve with nonoperative therapy alone, those who do not improve with conservative treatment have three options: continuous discomfort, full avoidance of pain-inducing activities, or surgical surgery.

Again, surgical alternatives for spondylolysis (as well as low-grade spondylolisthesis) should be reserved for people who have neurologic impairments, slip progression, or discomfort that limits everyday tasks. The literature on the best surgical process, strategy, and roles for decompression and instrumentation is still debatable. While there is still debate about the necessity for posterior decompression in individuals with just radicular symptoms, everyone agrees on the need for decompression when a real motor impairment is evident.

Furthermore, recent long-term follow-up from the SPORT database in the scenario of retrolisthesis and disc herniation at L5-S1 has indicated non-inferior outcomes in patients with surgically repaired disc herniations in the presence of retrolisthesis. The patient must understand that, while surgical intervention has a positive outcome for treating radicular pain, the prognosis for non-radiating lower back pain is less predictable.

Surgical Procedure

Spinal fusion is, in essence, a welding procedure. The primary concept is to fuse the afflicted vertebrae together so that they recover into a single, solid bone. A fusion removes mobility between the injured vertebrae and reduces spinal flexibility. According to the notion, if the uncomfortable spine segment does not move, it should not ache.

The doctor will initially realign the vertebrae in the lumbar spine during the surgery. Small bone grafts are then inserted into the gaps between the vertebrae to be united. The bones grow together over time, similar to how a fractured bone heals.

Your doctor may use metal screws and rods prior to putting the bone transplant to help stabilize the spine and boost the odds of successful fusion. In certain circumstances, individuals with high-grade slippage will also suffer spinal nerve root compression. If this is the case, your doctor may conduct a treatment to open the spinal canal and relieve nerve pressure before completing the spinal fusion.

Physical Therapy Management

Conservative treatment, including as physical therapy, rest, medication, and braces, should be used initially to treat spondylolisthesis. Rather of focusing just on muscular strength, the rehabilitation exercise program should aim to enhance muscle balance.

Good exercise choices include:

- Isometric and isotonic exercises are beneficial for strengthening the main muscles of the trunk, which stabilize the spine. These techniques may also play a role in pain reduction

- Core stability exercises are useful in reducing pain and disability in chronic low back pain in patients with spondylolisthesis.

- Movements in closed-chain-kinetics, antilordotic movement patterns of the spine, elastic band exercises in the lying position

- Gait training

- Stretching and strengthening exercises aim to reduce extension stresses on the lumbar spine caused by agonist muscle stiffness, antagonist muscle weakness, or both, which may result in reduced lumbar lordosis. Stretching exercises for the hamstrings, hip flexors, and lumbar paraspinal muscles are essential for improving the patient's mobility.

- Balance training includes - Sensomotoric training on unstable devices, walking in all variations, coordinative skills

Hydrotherapy - Endurance training of muscles is effective for chronic low back pain.

- Cardiovascular exercise - Athletes with spondylolysis and first-degree spondylolisthesis can participate in any sport. However, special consideration should be given to sports in which persistent injuries occur as a result of repetitive flexion, hyperextension, and twisting (e.g. gymnastics, aerobics, swimming in the dolphin technique). Athletes with a grade of 2, 3, or 4 can engage in all athletic activities, but only with a specific and specially tailored command. Sports with a low aerobic impact are strongly suggested. Walking, swimming, and cross-training are all sports that may be done. Although these activities will not help the shift, they are an excellent substitute for cardiovascular exercises. Running and other high-impact activities should be avoided if possible. Hyperextension and/or contact sports should be avoided by the teenage athlete or manual laborer.

Williams flexion exercises are a set of exercises that decrease lumbar extension and focus on lumbar flexion. These include

- Pelvic Tilts

- Partial sit-ups

- Knee-to-chest

- Hamstring stretch

- Standing lunges

- Seated trunk flexion

- Full squat

Differential Diagnosis

- Lumbosacral disc injuries

- Lumbosacral discogenic pain syndrome

- Lumbosacral facet syndrome

- Lumbosacral spine acute bony injuries

- Lumbosacral spine sprain/strain injuries

- Lumbosacral spondylolisthesis

- Lumbosacral spondylosis

- Myofascial pain in athletes

- Sacroiliac joint injury

Spondylolysis VS spondylolisthesis

A crack or stress fracture occurs through the pars interarticularis in spondylolysis (pars fracture). The pars interarticularis is a narrow, tiny section of the spine that links the upper and lower facet joints.

This fracture most usually occurs in the fifth lumbar vertebra, however it can also occur in the fourth lumbar vertebra. Fractures can happen on one or both sides of the bone. The pars interarticularis is the vertebra's weakest link. As a result, it is the area most prone to injury as a result of the repetitive stress and overuse that characterizes numerous sports.

Spondylolysis can develop in persons of various ages with no history of injury or engagement in sports. Patients with spondylolysis frequently have some degree of spondylolisthesis.

Conclusion

The majority of people with spondylolysis and spondylolisthesis get relief from pain and other symptoms within a few weeks or months. Most patients are able to progressively resume sports and other activities with little problems or recurrences.

Many individuals can benefit from a nonsurgical treatment plan that focuses on activity moderation. Patients should be aware that surgery does not always cure all pain because irreparable nerve damage has already happened.

The future of less invasive treatment alternatives will continue to improve spinal stenosis results. Outpatient endoscopic disc debridement followed by percutaneous instrumentation is now possible for certain patients and facilities because of advances in pain management and endoscopic technology.

The doctor may advise your kid to practice particular activities to stretch and strengthen the back and abdominal muscles to help avoid future damage. In addition, your child will require frequent check-ups to ensure that no complications arise.