Stenting Of COA

Overview

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) found that around 4 out of every 10,000 newborns born had coarctation of the aorta in a 2019 research that included data from 39 population-based birth defect monitoring programs from 2010 to 2014. This indicates that around 2,200 newborns are born in the United States each year with aortic coarctation. In other words, approximately 1 in every 1,800 newborns born in the United States each year is born with aortic coarctation.

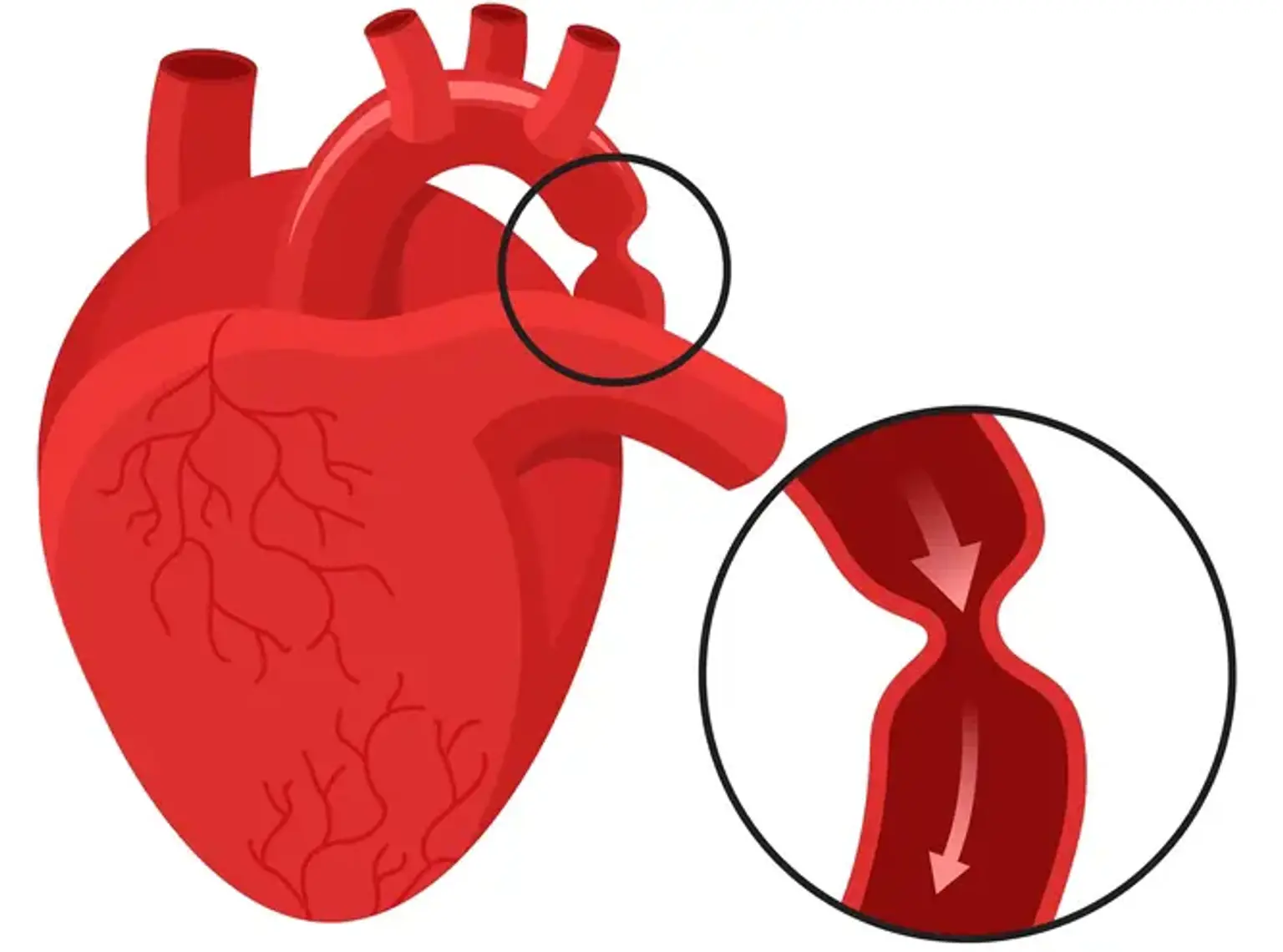

Coarctation of the aorta (COA) is a congenital cardiac defect. It indicates that the aorta is narrower than it should be. The aorta is a major artery that transports oxygen-rich blood from the left ventricle to the rest of the body. Because of this constriction, less oxygen-rich blood is delivered to the body.

The degree of constriction is variable. A young child with more aortic narrowing will have more symptoms. The symptoms will also appear at a young age. Coarctation can occur in infancy in some circumstances. Others may not see it till they are of school age or older. COA can be identified in infants, preschoolers, and teenagers. It is more common in men. If a family member has the condition, the chances of getting it are enhanced. It's also more common in some hereditary diseases, including Turner Syndrome. Aortic coarctation is frequently associated with other heart abnormalities. A bicuspid aortic valve is one of them.