Tracheostomy

Overview

Tracheostomy is one of the earliest known surgical operations, with images dating back to 3600 B.C. in ancient Egypt. A tracheostomy may be necessary in an emergency situation to bypass an obstructed airway, or it may be inserted electively to ease mechanical breathing, wean from a ventilator, or allow for more effective secretion management (referred to as pulmonary toilet), among other reasons.

Tracheostomy has traditionally been conducted as an open surgical surgery; however, safe and dependable percutaneous tracheostomy procedures have recently been developed, allowing for tracheostomy implantation at the bedside in many patients.

What is a Tracheostomy?

A tracheostomy is a hole in the front of the neck created during an emergency or scheduled operation. It creates an airway for those who are unable to breathe on their own, have difficulty breathing, or have a blockage that is impacting their breathing. People with diseases, such as cancer, may require a tracheostomy if their sickness is predicted to develop breathing issues shortly.

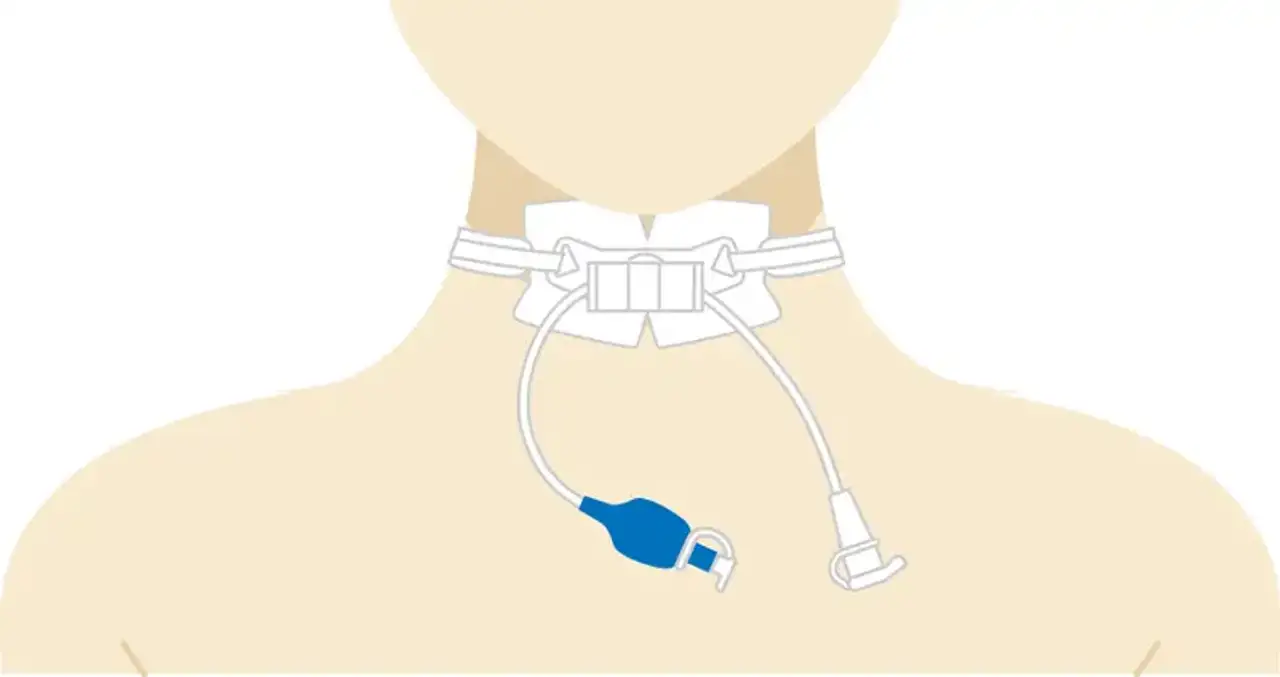

A hole is formed in the trachea during a tracheostomy operation (windpipe). A tube is then introduced through the hole into the trachea. The individual then breaths via the tube.

A tracheostomy may be required for a short period of time (temporary), but it may also be required for the remainder of a person's life (permanent):

- When there is a blockage or damage to the windpipe, a temporary tracheostomy may be administered. It can also be used when a person requires a breathing machine (ventilator), such as when suffering from severe pneumonia, a heart attack, or a stroke.

- If part of the trachea must be removed due to an illness such as cancer, a permanent tracheostomy may be required.

A tracheostomy is sometimes referred to as a "percutaneous" technique, which means it can be performed without the need for open surgery. A tracheostomy is frequently performed as a "bedside surgery" immediately in the room for patients who are in the emergency room or a critical care unit where they may be continuously monitored. It can also be performed as part of a scheduled surgical operation when other issues are addressed, such as during cancer surgery.

When you look at a tracheostomy opening (stoma), you may notice a portion of the trachea lining (the mucosa), which resembles the inside lining of your cheek. The stoma will appear as a hole on the front of your neck and may be pink or red in color. It is wet and warm, and it secretes mucus.

The respiratory system

The nose is coated with a mucus membrane that contains several blood veins close to the surface. As air flows through the nose, the blood vessels gather up warmth and moisture. This is significant because dry, chilly air hurts the lungs. Tiny hairs border the nose as well (called cilia). The cilia clean the air of debris and dust before it enters the throat and lungs.

The nose warms and moisturizes the air better than the mouth. The mouth also lacks cilia, which filter away debris and dust. The pharynx is where air enters after passing through the nose or mouth. The pharynx is the upper section of the throat behind the nose and mouth. The vocal cords are located in the larynx, which is the other section of the throat. The vocal cords vibrate as air travels through the larynx on its way out of the lungs. When you speak, the vibration creates the sounds.

The trachea is the tube-like structure responsible for transporting air from the neck to the lungs. As it enters the chest, the trachea splits into two tubes. The right and left main stem bronchi are the names of the tubes .

The trachea's two branches, like branches of a tree, split into smaller tubes that culminate in the air sacs. Through the air sacs, the body expel carbon dioxide and absorb oxygen. The esophagus is located behind the trachea. The esophagus is the tube that connects the mouth to the stomach. The trachea and esophagus are two distinct tubes.

Anatomic landmarks for tracheostomy:

- Thyroid notch - a palpable landmark to identify the superior aspect of the larynx in the midline.

- Cricothyroid membrane - a palpable depression between cricoid and thyroid cartilages. This is the location for an emergent cricothyrotomy.

- Cricoid cartilage is a tangible marker that marks the larynx-trachea junction. The skin incision is usually made 1-2cm below the cricoid.

- The sternal notch is a tactile marker that helps to locate the thoracic inlet. It is critical to palpate here for a high-riding innominate artery that may be encountered during tracheostomy.

Types of Tracheostomies

A tracheostomy can be either temporary or permanent, depending on the condition being treated.

If a tracheostomy is intended to be temporary, the length of time it is remained in place is determined by why it was performed and how long it will take to resolve the problem. For example, if a tracheostomy is required because radiation therapy is likely to cause tracheal damage, the trachea must recover before the tracheostomy may be removed. If a patient requires the assistance of a breathing machine, the issue that prompted the tracheostomy must be resolved before the tracheostomy may be removed. If the tracheostomy was performed owing to a blockage, accident, or disease, the tube will most likely be required for an indefinite amount of time.

If part of the trachea needs to be removed or if the issue does not improve, the patient may need to have a tracheostomy for the remainder of his or her life. The tracheostomy tube can be cuffed or uncuffed. The cuff is an inflatable closure inside the trachea that prevents air from leaking around the tube. It drives all air entering and exiting the lungs via the tube and prevents saliva and other liquids from mistakenly entering the lungs.

- When a patient is on a ventilator or requires the assistance of a breathing machine, a cuffed tube is frequently employed. The health care staff monitors the cuff pressure and makes modifications to the breathing equipment as needed.

- Uncuffed tubes are utilized for people who do not require a ventilator or breathing machine assistance. Some air can still travel around an uncuffed tube and up through the trachea to the larynx.

Depending on the nature and rationale for the tracheostomy, it may or may not contain an inside cannula. An inner cannula is a liner that can be locked into place before being opened and cleaned.

Reasons for a tracheostomy

The indications for tracheostomy can be divided among emergent tracheostomy and elective tracheostomy.

Indications for Emergent tracheostomy include:

- Acute upper airway blockage due to unsuccessful endotracheal intubation (foreign body, angioedema, infection, anaphylaxis, etc.)

- Post-cricothyrotomy (if a cricothyrotomy has been placed it should be immediately formalized into a tracheostomy once an airway has been secured)

- Penetrating laryngeal trauma

Acute airway blockage, such as aspiration of a foreign substance into the upper airway, Ludwig's angina, or penetrating damage to the airway that is not amenable to endotracheal intubation, is the most common reason for an emergent tracheostomy. Emergent tracheostomy may also be required in the case of severe face or cervical trauma, particularly in pan-facial fractures when craniofacial displacement precludes nasal intubation.

Indications for elective tracheostomy include:

- Prolonged ventilator dependence

- Prophylactic tracheostomy prior to head and neck cancer treatment

- Obstructive sleep apnea refractory to other treatments

- Chronic aspiration

- Neuromuscular disease

- Subglottic stenosis

The timing of elective tracheostomy for extended intubation (inability to wean from artificial ventilation) has been hotly debated. Tracheostomy should be performed 5-7 days following endotracheal intubation to reduce the risk of problems associated with long-term intubation, most notably subglottic stenosis.

If extubation is likely, the development of low-pressure cuffs on endotracheal tubes (with a maximum pressure of 20 cm H2O) may allow this period to be prolonged. Early tracheostomy, on the other hand, has been promoted in order to improve patient comfort, reduce sedation, and perhaps reduce ICU/ventilator days.

Early tracheostomy (3-7 days after intubation) is suggested for patients with severe closed head injuries or those who require extended ventilatory assistance. Similarly, several professional organizations urge tracheostomy at post-intubation day 5-7 in non-trauma patients with unsuccessful ventilator weaning. Tracheostomy may be required as a preventative measure for prolonged head and neck treatments owing to trauma or upper aerodigestive malignancies. Because edema from the operation or subsequent radiation therapy may indicate upper airway blockage, an elective tracheostomy is recommended before treatment begins.

Tracheostomy may be useful in refractory obstructive sleep apnea, particularly in morbidly obese patients who cannot be treated with continuous positive airway pressure. Patients with persistent neurological impairment may be unable to regulate their own oral secretions, putting them at risk of repeated aspiration. To prevent aspiration pneumonia, such a pulmonary toilet may necessitate an elective tracheostomy. Finally, individuals with neuromuscular diseases such as amyotrophic lateral sclerosis may lack the muscle power to breathe spontaneously, necessitating artificial ventilation via a tracheostomy.

Contraindications to Tracheostomy

Except for active cellulitis of the anterior neck skin, there are no definite contraindications to tracheostomy. Before performing a tracheostomy or any invasive operation on a terminally ill patient, end-of-life problems should be discussed and goals of continuing care defined.

Preparation

As previously stated, open tracheostomy is often performed in the operating room by a surgeon and supportive crew. Typically, the patient is intubated and sedated, however in cases such as Ludwig angina, a local anesthetic can be used and the tracheostomy performed while the patient is awake. Initially, a non-fenestrated cuffed tracheostomy tube is utilized. When aerosolization of respiratory secretions is a problem, the team must wear specialist personal protection equipment and the treatment must be conducted in a negative-pressure chamber.

Technique

- Open Tracheostomy

Thyroid notch, cricoid cartilage, and sternal notch are palpated and marked as anatomic landmarks. To discover a high-riding innominate artery, the surgeon should pay special attention to palpation in the sternal notch. A skin incision is then made 1 to 2 cm inferior to the carotid cartilage in the midline anterior neck. An incision can be made horizontally or vertically.

Thyroid notch, cricoid cartilage, and sternal notch are palpated and marked as anatomic landmarks. To discover a high-riding innominate artery, the surgeon should pay special attention to palpation in the sternal notch. A skin incision is then made 1 to 2 cm inferior to the carotid cartilage in the midline anterior neck. An incision can be made horizontally or vertically.

Stay ligatures may be applied laterally to aid in tracheal traction during tube implantation and tube security in the postoperative phase. A tracheostomy tube is implanted when an incision is made between the second and third rings. Several modifications have been proposed, including the removal of an anterior window of cartilage (often removing a segment of 1 to 2 rings), the use of a vertical anterior incision across 1-2 rings (used in pediatric tracheostomy), or the creation of a Bjork flap, which involves the creation of an inferiorly-based cartilage flap and its attachment to the subcutaneous tissues.

To reduce the chance of future stenosis, the first ring is avoided. The tube is linked to the anesthetic circuit and end-tidal CO2 is verified. The cricoid hook is only then freed. The tracheostomy tube is sutured to the anterior neck skin and secured with a gentle trans-cervical knot until the first tracheostomy tube replacement on postoperative day five. - Percutaneous Tracheostomy

Ciaglia and colleagues described a percutaneous method in 1985. Under bronchoscopic supervision, a dilatational procedure is used using a modified Seldinger technique. Numerous research have been conducted to compare the outcomes of the two procedures, indicating some possible benefits of one technique over the other. The percutaneous approach is more suitable for bedside use, as it avoids transporting potentially critically sick patients to the operating room.

The percutaneous approach has also been linked to decreased blood loss and infection rates when compared to the open procedure. The percutaneous approach has been linked to multiple serious and sometimes fatal consequences, including tracheal laceration, aortic damage, and esophageal perforation, which are exceedingly uncommon following the open treatment.

Possible complications

Complications following tracheostomy are best thought of as happening during the surgical, early postoperative, and late postoperative periods.

- Operative Period

Bleeding is the most frequent intraoperative complication. Many tracheostomy patients are critically unwell and have an underlying coagulopathy that should be addressed preoperatively if feasible. If they are thrombocytopenic, they may need a platelet transfusion to platelets more than 50,000 before undergoing any airway surgery.

Anatomically, the anterior jugular veins may normally be retracted laterally; however, if there are any abnormal or bridging anterior jugular veins, they should be ligated. A thyroidia ima artery, which runs along the anterior surface of the trachea, will be present in roughly 5% of individuals. Once separated, it can regress inferiorly and contribute to continued bleeding, therefore it must be ligated with care. As previously stated, meticulous ligation of the thyroid isthmus using transfixing ligatures can reduce the danger of bleeding from this location.

Airway fire is an uncommon yet devastating intraoperative complication. This is owing to the presence of high amounts of oxygen in the anesthetic tubing and the electrocautery unit's ignition source. This may be avoided by clear communication between the surgical and anesthesia teams. If there is a fire, the entire circuit should be disconnected from the patient and the patient should be bagged with a mask until the tracheostomy is placed. Laryngoscopy, bronchoscopy, and esophagoscopy should then be used to check the aerodigestive tract for any potential heat damage.

A pneumothorax or pneumomediastinum is a final surgical complication. If the tracheostomy tube is put anterior to the trachea, this might result in the unintended development of a false channel. A pneumothorax can also be caused by a burst bleb or damage to the apex of the lung.

If the pneumothorax is a problem, a chest radiograph should be acquired postoperatively, and a chest tube should be implanted if required. Although some surgeons take postoperative chest X-rays on all tracheostomy patients, this is relatively unusual following a regular tracheostomy. - Early Complications

Infections following a tracheostomy are extremely rare, and those needing antibiotics are even rarer. The majority of "infections" are routinely addressed with local wound care since they are just leaking of secretions from the new stoma into the field. Some deep infections or frank abscesses may need drugs specific to the infecting organism, which is more common in immunocompromised patients.

Acute tracheostomy tube occlusion can be caused by blood or mucus and is more common in the immediate and early postoperative periods. Postoperative practices that include planned flexible tracheal suctioning, humidified oxygen usage, and daily replacement or cleaning of the inner cannula can reduce the likelihood of full blockage. Tube dislodgement can also cause acute blockage, in which the distal tip of the tracheostomy tube escapes the tracheal lumen and rests in soft tissue, sometimes known as a false-passage.

Stay sutures placed in the lateral trachea during the operating procedure, as well as skin sutures to attach the tracheostomy tube to the neck skin while the fistula grows, can help with tube replacement. Reintubation may be necessary to re-establish a definitive airway and is best accomplished by flexible laryngoscopy through the tracheostomy tube to visually check intra-lumenal insertion. - Late Complications

The most feared late consequences include pressure necrosis caused by over-inflation of the tracheostomy tube cuff. Because of developments in low-pressure cuffs and increased awareness of cuff pressure as a danger issue, they are becoming less used. To avoid this, tracheostomy cuff pressure should be checked on a regular basis, ideally at a maximum of 20cm H2O. Ischemia can cause tracheal necrosis if there is too much pressure in the trachea. Scanning and stenosis develop from subsequent healing.

A formal examination of the many treatment options for stenosis, both endoscopic and open, is beyond the scope of this article. - Persistent Tracheocutaneous Fistula

When the tracheostomy tube is removed, the stoma normally closes spontaneously within 24-48 hours. Granulation tissue can sometimes remain at the location and be a nuisance. This is usually treatable with topical silver nitrate. If surgical closure is necessary, debridement and layer closure using the strap muscles to support the repair are typically effective. - Tracheoesophageal Fistula

Tracheoesophageal fistula is an extremely uncommon complication that occurs in fewer than 5% of tracheostomies. They are typically caused by severe pressure on the posterior membranous trachea (the party wall shared by the trachea and esophagus). This can be caused by over-inflation of the tracheostomy tube cuff. If the tracheostomy tube is orientated posteriorly, excessive pressure is placed on the posterior tracheal wall. If ventilatory pressures are greater than predicted, a flexible scope should be put through the tracheostomy tube to guarantee correct intra-lumenal orientation of the tracheostomy tube.

The presence of an indwelling nasogastric tube, in addition to the inflexible tracheostomy tube, raises the risk of this problem, therefore alternative enteral feeding (gastrostomy tube) is recommended for patients who require tracheostomy. Patients with tracheoesophageal fistulas may have bronchopulmonary suppuration, tracheobronchial contamination with food/gastric contents, or simply recurring or severe pneumonia. The fistula is typically 1-4 cm long and requires treatment to both the trachea and the esophagus.

Resection of the fistula with primary esophageal closure, primary anastomosis of the trachea, and interposition of a viable muscle flap results in definitive repair.

Conclusion

A tracheostomy offers a stable, long-lasting airway for patients who require artificial ventilation for an extended period of time. It can also serve as a pulmonary toilet for people who are unable to discharge secretions. Depending on the rationale for its usage, a tracheostomy might be temporary or permanent. In general, a surgeon will not perform a tracheostomy unless there are no other options.