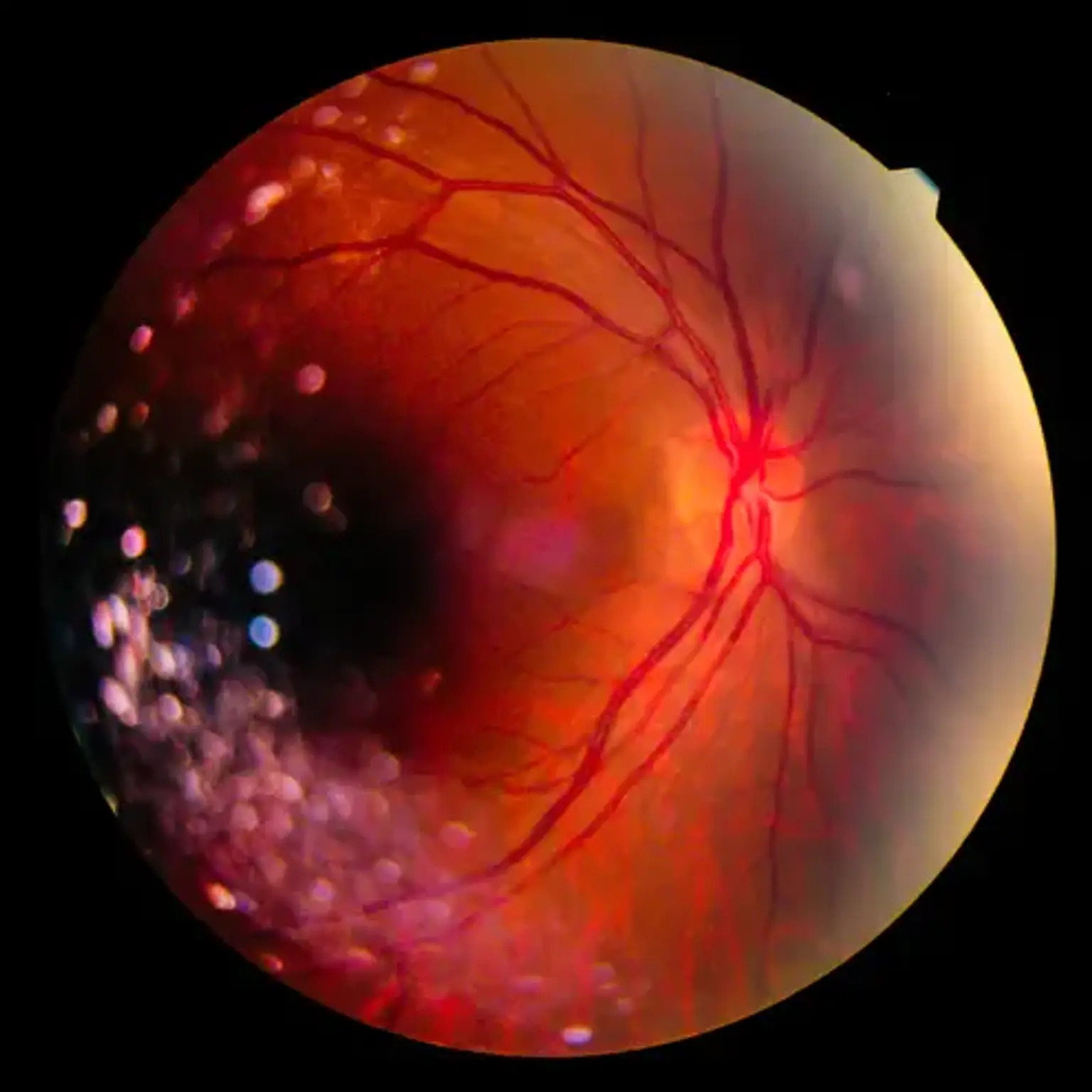

Vitreoretinal disease

Overview

Your eye is made up of numerous distinct components that absorb light and deliver signals to your brain. How well your eyes operate and how healthy they are reliant on each of these components working properly. If you have an infection or condition in one of your eyes, you may have discomfort and vision problems such as seeing halos. It can have an effect on your visual acuity in some situations.