Cholelithiasis

Overview

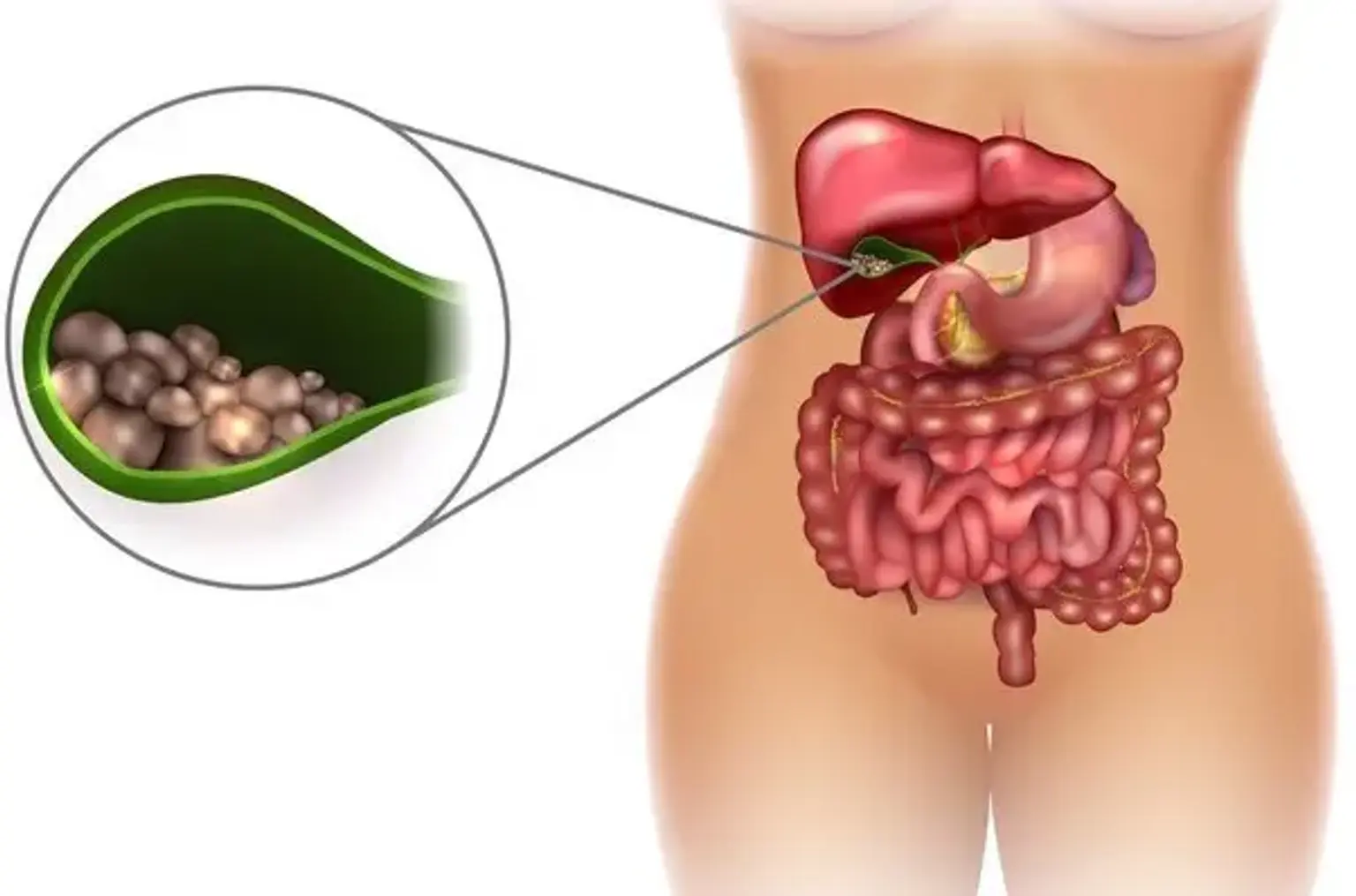

Gallstones, also known as cholelithiasis, are hardened deposits of digestive fluid that can form in your gallbladder. The gallbladder is a tiny organ found directly below the liver. The gallbladder stores bile, a digestive fluid that is discharged into the small intestine. Gallstones affect 6% of men and 9% of women in the United States, with the majority of cases being asymptomatic. The chance of developing symptoms or consequences in persons with asymptomatic gallstones identified inadvertently is 1% to 2% every year.

Asymptomatic gallbladder stones discovered in a healthy gallbladder and biliary tree do not require treatment unless they cause symptoms. However, after 15 years of follow-up, roughly 20% of these asymptomatic gallstones will develop symptoms. Complications from gallstones include cholecystitis, cholangitis, choledocholithiasis, gallstone pancreatitis, and, in rare cases, cholangiocarcinoma.