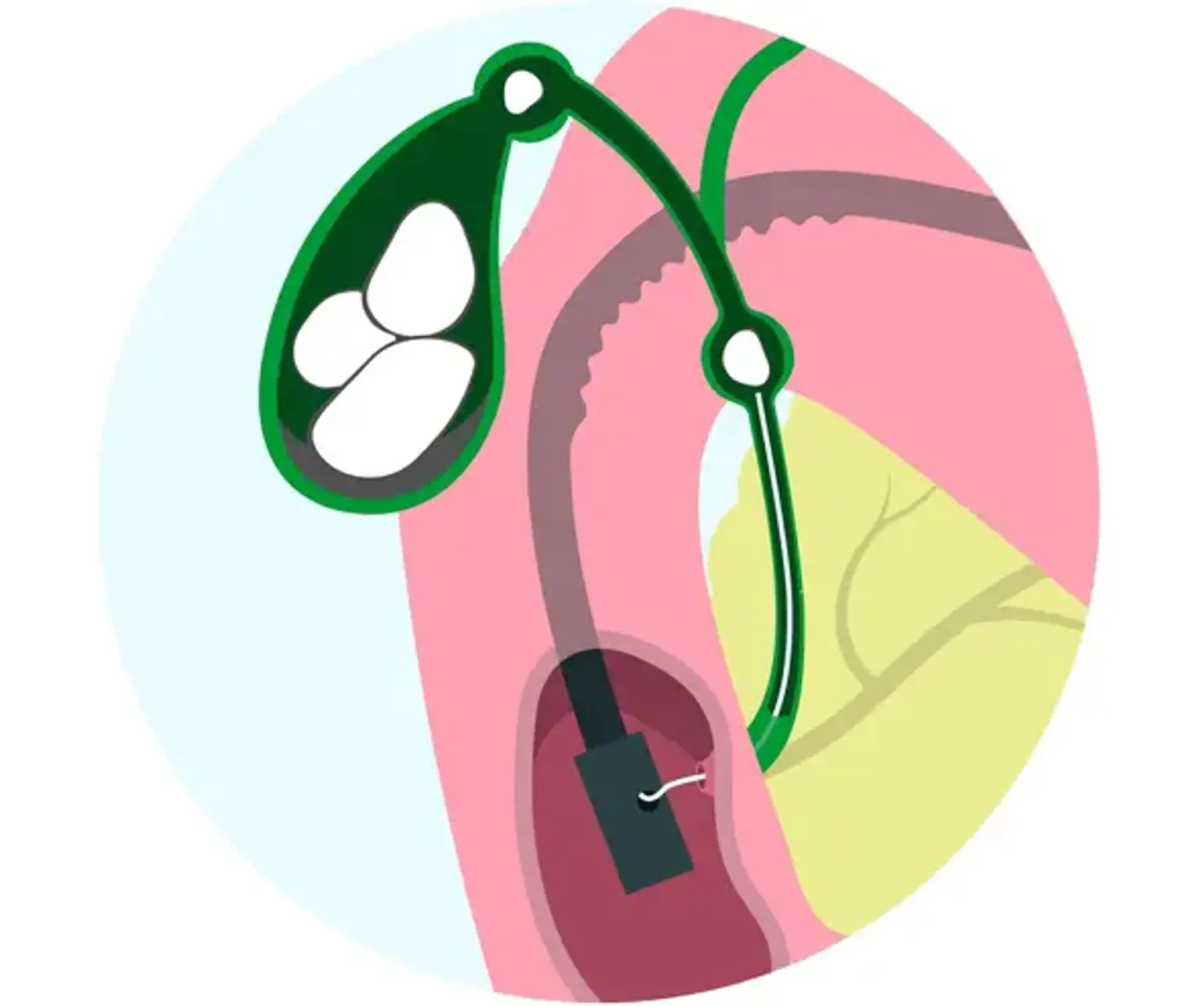

Endoscopic Choledochoduodenostomy

Overview

Endoscopic ultrasonography (EUS) is a therapeutically important technique not only for diagnostic purposes during EUS-guided fine needle aspiration, but also for interventional purposes. Endoscopists with experience devised and conducted EUS-guided biliary drainage. In patients with biliary blockage, EUS-guided choledocoduodenostomy (EUS-CDS) is a rather well-established alternative biliary drainage procedure for biliary decompression.