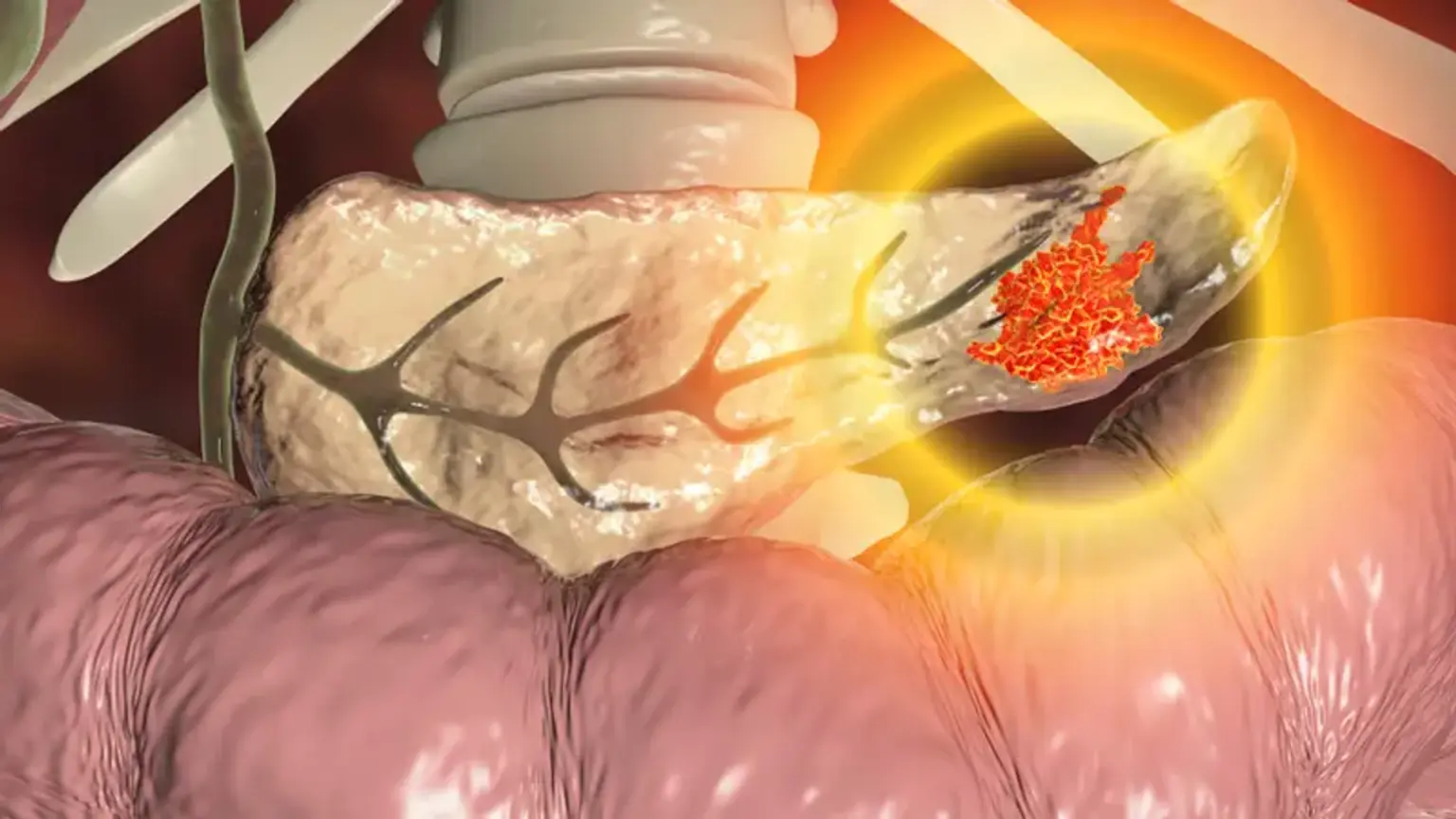

Endoscopic Pancreatic Necrosectomy

One of the most serious side effects following a case of severe acute pancreatitis is walled-off necrosis. A quarter of individuals with walled-off necrosis may need interventional drainage or debridement, even though many of them can be treated conservatively. Percutaneous drainage is typically chosen as the initial course of treatment, with open surgery being an alternative if necrosectomy is necessary. These two procedures are not advised as the first line in modern practice due to the aggressiveness of open surgery and the danger of pancreatico-cutaneous fistula from the percutaneous method (unless internal drainage or pancreatic duct bridging by an internal stent is performed). New minimally invasive procedures have been increasingly effective during the past ten years, including endoscopic pancreatic necrosectomy and video-assisted retroperitoneal debridement.