Forward head posture

What is Forward head posture?

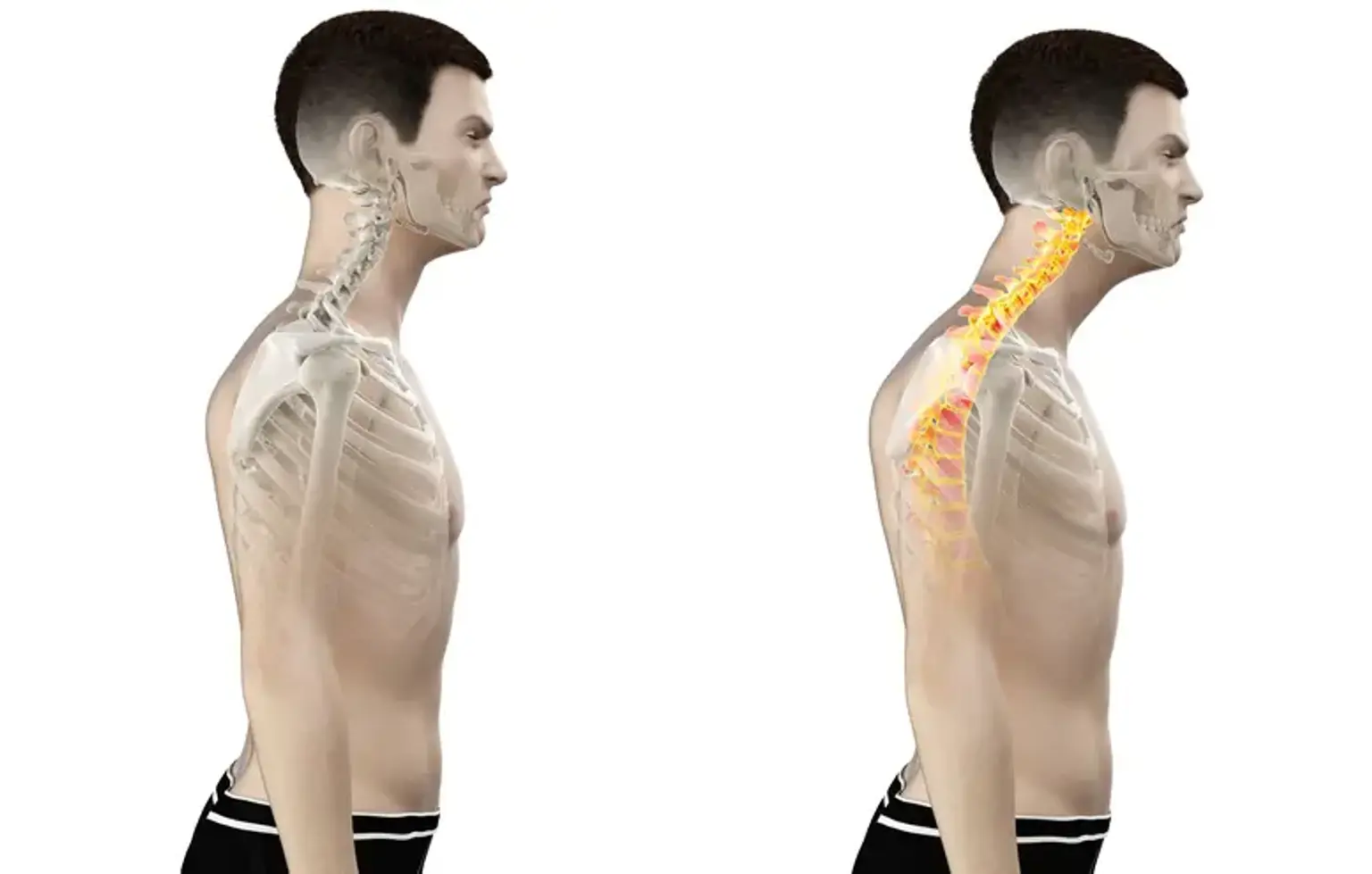

Forward Head Posture (FHP) is a frequent condition in which your head is positioned with your ears in front of your body's vertical midline. Your ears should line up with your shoulders and midline in normal or neutral head position. Because it is caused by prolonged bending toward a computer screen or hunching over a laptop or mobile phone, FHP is also known as "text neck" or "nerd neck." It is also linked to the ageing process's decrease of muscular strength.

FHP can result in neck pain, stiffness, an uneven stride, and other adverse symptoms. It is also frequently accompanied with rounded shoulders, sometimes known as kyphosis. The good news is that it is typically fixable: stretching and strengthening exercises, together with excellent posture, reduce adverse effects and restore improved posture.