Heart valve disease

Overview

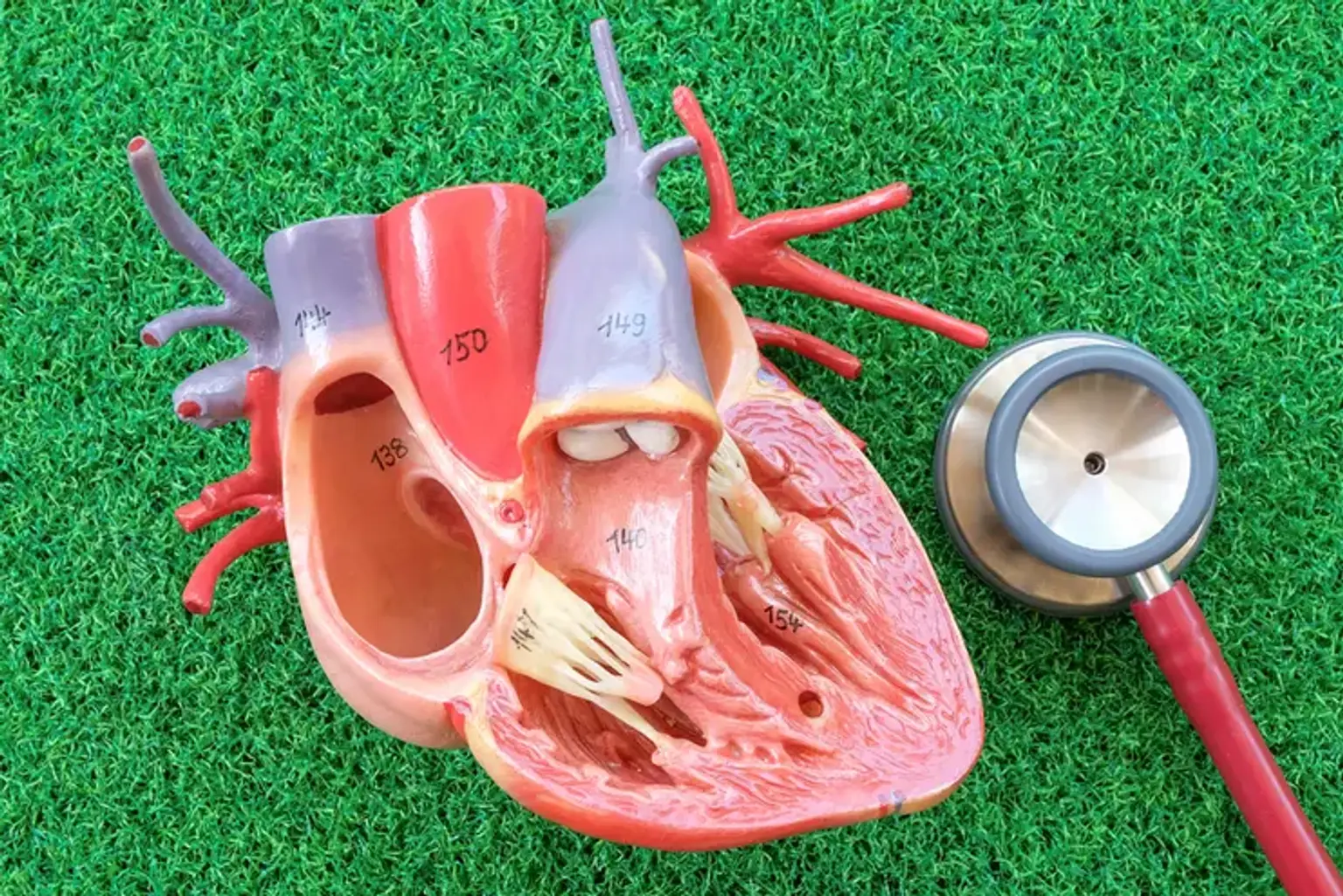

Valvular heart disease (VHD) refers to a group of prevalent cardiovascular disorders that account for 10% to 20% of all cardiac surgical operations performed in the United States. A greater understanding of the natural history, along with significant breakthroughs in diagnostic imaging, interventional cardiology, and surgical methods, has resulted in more accurate diagnosis and patient selection for therapeutic procedures.

A detailed understanding of the various valvular abnormalities is required to assist in the care of VHD patients. A thorough history for evaluation of causes and symptoms, accurate assessment of the severity of the valvular abnormality by examination, appropriate diagnostic testing, and accurate quantification of the severity of valve dysfunction, as well as therapeutic interventions, are all part of an appropriate work-up for patients with VHD.

In assessing outcomes, it is also critical to determine the role of treatment interventions against the natural course of the illness. Infective endocarditis prophylaxis is no longer suggested unless the patient has a history of endocarditis or a prosthetic valve.