Pediatric voiding dysfunction

Overview

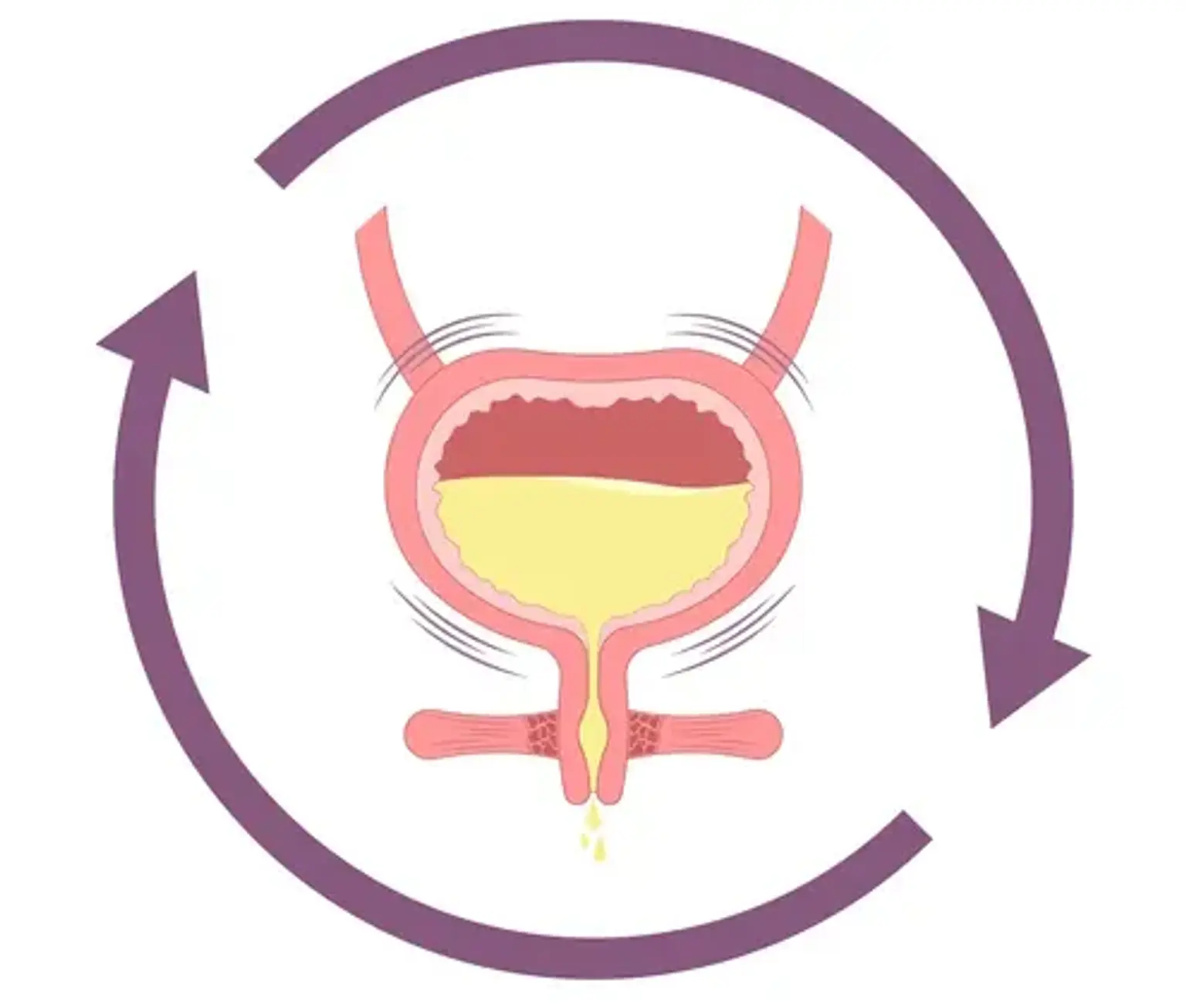

Going to the toilet may appear to be a straightforward task, but there is a complex set of signals that ensure the bladder performs precisely what the brain tells it to do. Children may have difficulty retaining their pee if any of these signals is out of sync (urinary incontinence). If a kid over the age of four experiences urine incontinence and doctors are unable to pinpoint a particular anatomical or neurological reason, the child may be diagnosed with voiding dysfunction.

No one understands what causes voiding disorder, but the illness can have a physical, social, and psychological impact on children. Some kinds of voiding dysfunction, if left untreated, can result in vesicoureteral reflux (VUR) and long-term kidney damage.