Uterine Myoma

Overview

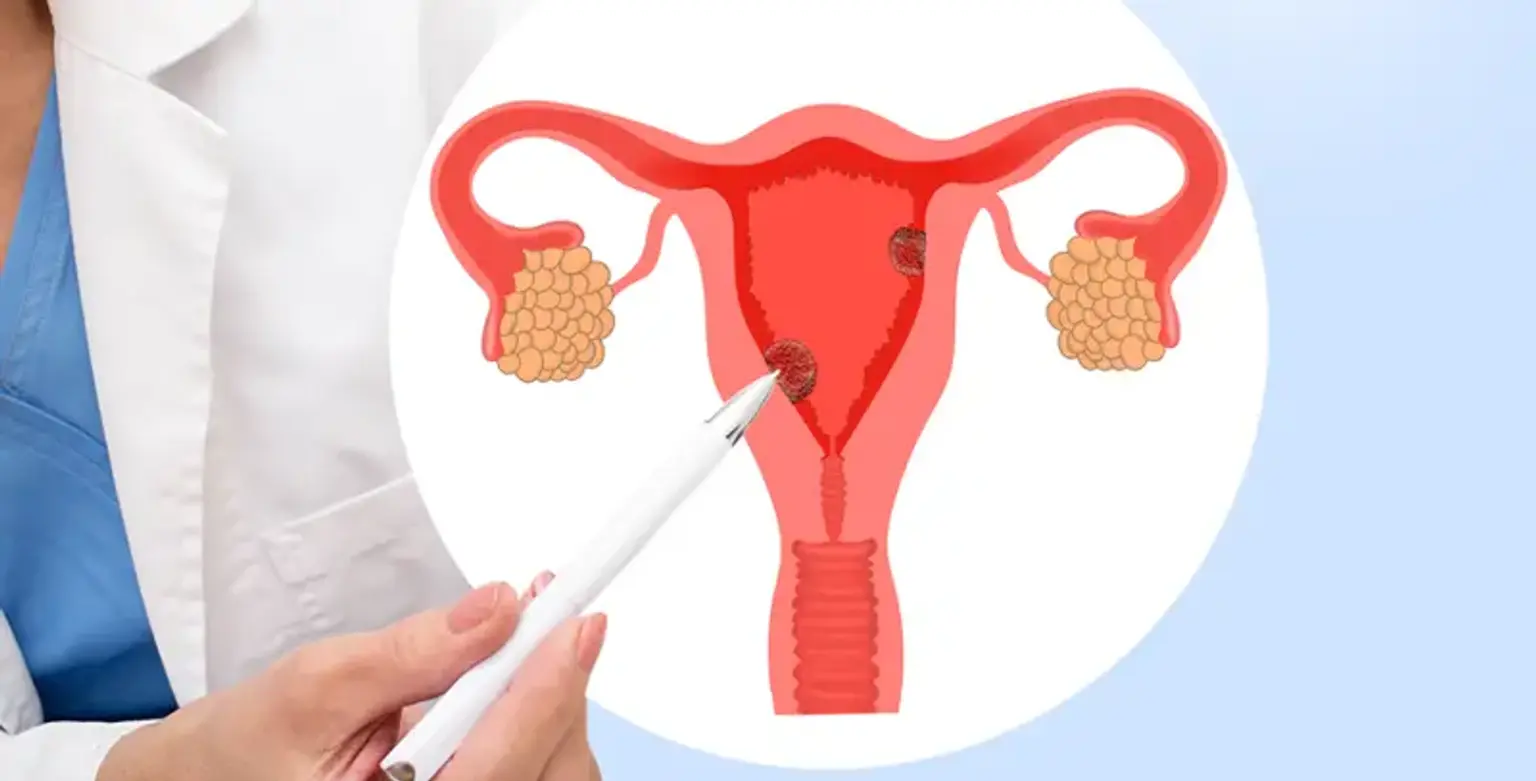

Uterine Myomas are non-cancerous smooth tumors that can grow in or around the uterus. Myomas, which are partially made of muscle tissue, seldom form in the cervix, but when they occur, they are generally accompanied by myomas in the larger, upper region of the uterus. Fibroids and leiomyomas are other names for myomas in this area of the uterus.